aka Star Wars Episode IV: The New Hope

USA. 1977.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – George Lucas, Producer – Gary Kurtz, Photography – Gilbert Taylor, Music – John Williams, Photographic Effects Supervisor – John Dykstra, Models – Colin Cantwell, Animation – Peter Kuran, Computer Animation – Larry Cuba, Stop Motion Animation – Jon Berg & Phil Tippet, Mechanical Effects – John Stears, Makeup – Rick Baker, Doug Beswick, Graham & Kay & Stuart Freeborn, Nick Maley & Christopher Tucker, Production Design – John Barry. Production Company – Lucasfilm/20th Century Fox.

Cast

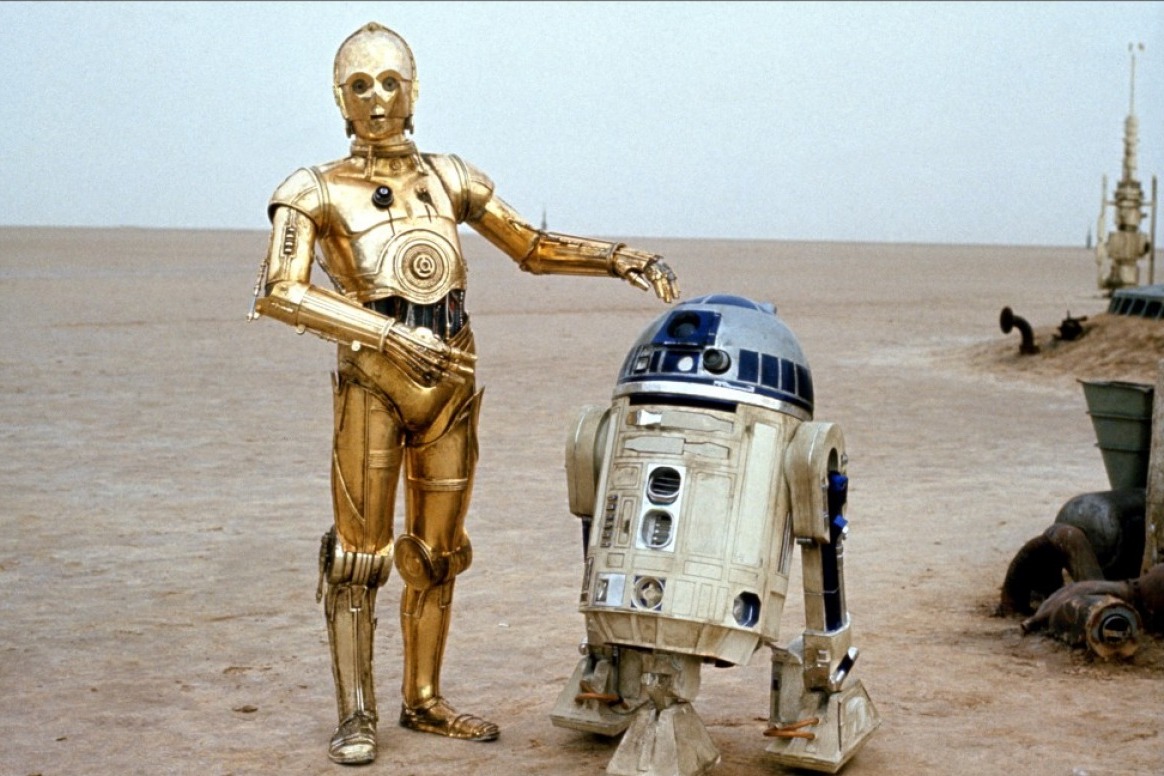

Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker), Harrison Ford (Han Solo), Carrie Fisher (Princess Leia Organa), Alec Guinness (Obi-wan Ben Kenobi), David Prowse (Darth Vader), Peter Cushing (Grand Moff Tarkin), Anthony Daniels (C3PO), Kenny Baker (R2D2), Peter Mayhew (Chewbacca), James Earl Jones (Voice of Darth Vader), Phil Brown (Owen Lars), Shelagh Fraser (Aunt Beru)

Plot

In a galaxy far, far away. The forces of the Empire, headed by Darth Vader, capture Princess Leia Organa of the intergalactic Rebellion. She leaves all-important information about the flaws in the Empire’s top-secret weapon The Death Star in the company of two droids C3PO and R2D2. The droids flee in an escape pod down to the surface of the remote desert planet Tattooine. They are captured by native Jawas and sold into the company of naive young farmboy Luke Skywalker who dreams of joining the Rebellion. Luke accidentally uncovers a hologram left inside R2D2 by Princess Leia for former Jedi Knight Obi-wan Ben Kenobi. Meeting Ben Kenobi, Luke realises that his aunt and uncle have been keeping the truth about his father, who was a Jedi Knight, from him. When Vader’s forces kill his aunt and uncle, Luke joins Ben Kenobi as he sets out to answer the princess’s call. Ben starts to teach Luke to understand his mystical powers as a Jedi. Hiring the services of the space pilot Han Solo, they set off to save the princess and stop the Death Star before it destroys the Rebel stronghold.

When Star Wars came out in 1977, it could only be described as a phenomenon. It was a phenomenon that took off like nothing else, carried solely by word of mouth. It was something the box-office had not seen before. It was a surprise even to its creator George Lucas who had spent four years shipping the script around the studios and racking up rejections and who expected Star Wars would only be seen by a few die hard science-fiction fans, not to become the (then) highest grossing film of all time.

It had been a production racked with problems – between Lucas and the facility he created at Industrial Light and Magic who initially spend millions of dollars without producing any usable film; between Lucas’s friends and studio heads who did not understand the script and reacted badly to a work print of the film; hostility between Lucas and the English production crew; hostility between a characteristically withdrawn and uncommunicative Lucas and his cast. Indeed, in the expectation that Star Wars would be a flop, Lucas, instead of attending the premiere, took a holiday in Hawaii with his good friend Steven Spielberg where the two of them sat on the beach and cooked up a small idea for an adventure film that would later become Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

The success of Star Wars was a phenomenon. It was not just the round-the-block queues; it was the associated phenomena – Star Wars comic-books, lunchboxes, posters, face masks, toys. John Williams symphonic score even made it into the pop charts and Star Wars was nominated for a Best Picture Academy Award. More importantly, science fiction and epic fantasy suddenly became respectable and we entered a colossal boom where science-fiction/fantasy became one of the highest box-office earning forms of box-office genre, a trend that is still with us today and shows no sign of slowing down.

To understand the phenomenon that was Star Wars, it has to be placed in perspective. Star Wars came at the end of a decade where science-fiction had retreated into a nihilistic vision of a future that held no hope – with films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Colossus: The Forbin Project (1969), The Andromeda Strain (1971), Westworld (1973), The Terminal Man (1974), indeed George Lucas’s own first film, the dystopian effort THX 1138 (1971). All of these saw a vision of the future where scientific perfection had overrun everything, where technology was triumphant and mankind a disease that flawed its white-on-white perfectionism. Humanity had little in the way of hope to cling onto, be it left with saving the last forests – Silent Running (1972), the last seeds – The Ultimate Warrior (1975), living in a badly crowded, overpopulated world – Soylent Green (1973), or simply struggling to hold onto one’s individuality – Rollerball (1975), and where the universe itself seemed cold and alone in its vastness – The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and tv’s Space: 1999 (1975-7). Mainstream cinema too was filled with such nihilistic doom laden voices as Dirty Harry (1971), Death Wish (1974), The Godfather (1972), The Exorcist (1973) and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976). In contrast, Star Wars offered a return to an old-fashioned black-and-white fairytale morality that caught one up in the epic sweep of heroism, adventure and derring-do, a dash of romance and above all the purest shot of that goshdarn sense of wonder that every science-fiction fan feels about the eight of fourteen when science-fiction can suddenly catapult one out of their mundane life into epic adventures on a galactic scale.

Whatever you want to detract from Star Wars‘s success – and many have picked on its simplicity (the cracker-box Zen mysticism of The Force), or the scientific flaws (when Han Solo says “We did the Kessel Run in under 3.5 parsecs” he is mistakenly using a unit of interstellar distance (one parsec equals 3.26 light years) as one of speed; it is akin to saying “We drove from Los Angeles to New York in under twenty miles”) – what you cannot deny is that Star Wars was a success. No film before managed to take science-fiction to such an amazingly broad cross-section of the media, indeed to legitimise it, with the success that Star Wars did.

Star Wars reads like a collage of science-fiction influences. It is less a story than it is a pastiche of Saturday matinee genres from George Lucas’s childhood. People swashbuckle with swords of light; there is a bar of lowlifes that could have come out of any Western but is instead filled with alien faces. When Industrial Light and Magic were designing the Death Star trench sequence, Lucas edited together dogfight sequences from WWII films like The Dam Busters (1954), The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1954) and 633 Squadron (1964) to show them what he wanted. The basic plot of Star Wars has been accused of being stolen from Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress (1958). George Lucas had originally intended to make a Flash Gordon film but ended up making his own story when the rights proved to be too expensive to obtain. (There is still a large element of Flash Gordon‘s influence – most notably in Princess Leia and her buns of hair, which are taken direct from a character called Princess Freia in the Flash Gordon comic-book).

There are all manner of science-fiction in-jokes – the mutant from This Island Earth (1955) makes an appearance as a musician in the background of the cantina scene and there is a giant sandworm skeleton in the deserts of Tattooine in a reference to Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965), while the character of C3PO could almost have been designed as a male equivalent of the android Maria in Metropolis (1927). Part of the universality of Star Wars is that it slots into an instant recognisability – George Lucas claims to have based the storyline for the series on the universal myth archetypes of Joseph Campbell. Star Wars is mythic adventure that rests in a bed of half-recognised scenes from other films that it then uses to chart its own heroic adventure – it is as much an adventure as it is an adventure through some shared childhood.

What was apparent was the changes that Star Wars wrought in science-fiction. Science-Fiction went from a vision of an inhospitably alone universe to a thoroughly lived-in one whose inhabitants took the miraculous for granted; production design of the future went from pristine antiscepticism to a lived-in world that was running down at the edges; robots went from dangerous A.I.’s conspiring against humanity to cute anthropomorphic sidekicks that did a Laurel and Hardy routine; aliens were no longer vast, threatening forces from out of a hostile universe but merely ugly mugs in a barroom that humanity had so managed to intermingle with that co-relationship was taken for granted; and spaceflight was less a bold, fearsome breaking of new frontiers than it was something being conducted by kids not unakin to the hod-rodders in Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973). Going beyond the fear of post-2001 science-fiction that technology will swallow us up, George Lucas’s answer was in having Luke Sykwalker find tranquility at the climax by turning off his targeting computer and relying on The Force – essentially saying that computers will only take us so far and thereafter we must rely on intuition.

Perhaps what made Star Wars such an enduring classic – and there is no doubt about this for when Empire magazine conducted an All-Time Best readers poll in 1997, Star Wars emerged as the No. 1 film – is less to do with myth and pastiche than it is simply out-and-out entertainment. Perhaps one of the finest examples of what one refers to as ‘sense of wonder’ comes in the opening shot where a tiny ship comes zipping across the top of the screen pursued by blaster bolts, which is followed a moment later by a colossal Star Destroyer that is so big it keeps on coming. The thrill of that shot – the contrast of scales moving from the small to the vast, the rumble that vibrates right throughout the theatre – is the essence of what science-fiction is about.

Star Wars is filled with many of these peaks of exhilaration – the scene where the Millennium Falcon finally breaks through into hyperspace always makes an audience break out into cheers. The climax with the tiny rebel fighters ducking and diving to attack the Death Star is one of the most exhilarating of all screen action sequences. (Amusingly the studio wanted to cut the sequence for cost reasons and make the escape from the Death Star with princess be the film’s climax). Star Wars is a film whose effect is immeasurable. It created an entire special effects industry; it is one that single-handedly made science fiction box-office gold and created a boom that lasts to this day; and above all it created a whole generation of science-fiction fans – I know it did me.

Star Wars was followed by two sequels:– The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983), where George Lucas revealed that Star Wars was in fact part of a giant nine film saga of which these three were respectively Episodes IV-VI. Accordingly, in 1980 re-release, Star Wars was retitled Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. George Lucas retired from active directing following Star Wars and turned subsequent entries over to other writers and directors. The series was thought to be over following Return of the Jedi but two decades later Lucas successfully revived it again with a new trilogy, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999), Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) and Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005), where he also returned to the director’s chair. In 2012, George Lucas announced his retirement and a deal wherein he sold the Star Wars franchise to Disney who produced a new trilogy consisting Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens (2015), Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi (2017) and Star Wars Episode IX: Rise of the Skywalker (2019), featuring the principal actors from the first film. These were interspersed with a series of live-action spinoff films featuring various supporting characters with Rogue One (2016) and Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018), as well as the tv series’ The Mandalorian (2019- ), The Book of Boba Fett (2021-2), Andor (2022- ), Obi-wan Kenobi (2022), Ahsoka (2023- ) and The Acolyte (2024).

Other spinoffs were The Star Wars Holiday Special (1978), a dismal tv movie that treats Star Wars as a cabaret act and is most notable for introducing the character of Boba Fett in a twenty minute animated sequence. The Ewok Adventure/Caravan of Courage (1984) and Ewoks II: The Battle of Endor/Ewoks and the Marauders of Endor (1986) were two tv movies, released cinematically outside of the USA, featuring the small furry creatures introduced in Jedi. Droids (1985-6) and Ewoks (1985-7) were also two animated tv series set in the universe, while Star Wars: Clone Wars (2003-5) was a series of five-minute animated episodes that aired on the Cartoon Network. This was later extended as an animated film Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008), which was the flagship for an animated tv series Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008-14). The Disney inheritance of the series copyright has also resulted in a further animated series Star Wars: Rebels (2014– ).

In 1997, to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the film, George Lucas re-released the trilogy with digitally re-remastered footage, under the umbrella rubric The Star Wars Trilogy – The Special Edition. Star Wars was re-released with many scenes touched up to eliminate matte lines and boost the quality of the effects shots. This proved highly disappointing as many of the new flashy, digital effects heavy scenes ended up distracting and detracting from the existing material – the most notable example being the scene where Luke and Ben are stopped by Stormtroopers when entering Mos Eisley, where one is so distracted by rearing banthas in the background and the city stretching out that what the scene is about dramatically swamped. The Special Edition also adds one scene about a minute long originally shot but not included in Star Wars where Han Solo meets Jabba the Hut. This was originally shot with an actor who is replaced by a digital Jabba for the Special Edition.

Star Wars was parodied in:– Hardware Wars (1977), Morons from Outer Space (1985), Spaceballs (1987), The Nutty Professor II: The Klumps (2000) and the Blue Harvest episode of Family Guy (1999– ). The films that it is referenced in are innumerable – from almost all of the works of Kevin Smith, notably Zack and Miri Make a Porno (2008), which depicts the shooting of a pornographic parody, to tiny models of R2D2 placed in the background of the mothership in Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), jokes and references in E.T. – The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), The Pirate Movie (1982), D.C. Cab (1983), V (1983), Back to the Future (1985), The Big Bang (1987), Big and Hairy (1998), The X Files (1998), Black Knight (2001), Team America: World Police (2004), Robots (2005), Planet 51 (2009), The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (2010), Arthur (2011), The Fades (2011), Ted (2012), Machete Kills (2013), The Lego Movie (2014), Dudes & Dragons (2015), Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018) to even the naming of Ronald Reagan’s proposed real world satellite defence program Star Wars. There are even jokes about Star Wars fandom in films like Free Enterprise (1998), Race to Witch Mountain (2009), 17 Again (2009), Gulliver’s Travels (2010) and Dead Snow 2 (2014). Of particular interest here is Fanboys (2008), a witty comedy about Star Wars that contains some extremely funny Star Wars in-jokes, and the documentary The People vs. George Lucas (2011) about fans unhappiness of the directions in which George Lucas has taken the Star Wars series. Elstree 1976 (2015) is a documentary about the bit players and extras that appeared in the film. 5-25-77 (2022) is an autobiographical film about how a young teen wannabe filmmaker visited the ILM studio during shooting and was shown uncompleted test scenes from Star Wars that ended up changing his life. There has also been an entire industry of unofficial Star Wars fan films and parodies released on the internet in recent years. Of interest here is The Man Who Saves the World (1982), more commonly known as The Turkish Star Wars, a film which is substantially made up of effects footage stolen from Star Wars and other films, which has gained a bad movie reputation in recent years.

Outside of the Star Wars series, George Lucas’s only other genre film as director has been the interesting and very different dystopian work THX 1138 (1971). George Lucas’s other genre works as producer are:– the Indiana Jones series – Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023); the animated animated film Twice Upon a Time (1983); the disastrous Howard the Duck (1986); the fine Jim Henson fantasy Labyrinth (1986); the sword-and-sorcery adventure Willow (1988); and the animated Strange Magic (2015).

Trailer here

Reissue trailer here:-