Crew

Director/Screenplay – George Lucas, Producer – Rick McCallum, Photography – David Tattersall, Music – John Williams, Visual Effects – Industrial Light and Magic, Visual Effects Supervisors – John Knoll, Dennis Muren & Scott Squires, Digital Supervisor – David Dorovitz, Animation Director – Rob Coleman, Special Effects Supervisors – Geoff Heron & Peter Hutchinson, Production Design – Gavin Bocquet, Design Director – Doug Chiang. Production Company – Lucasfilm.

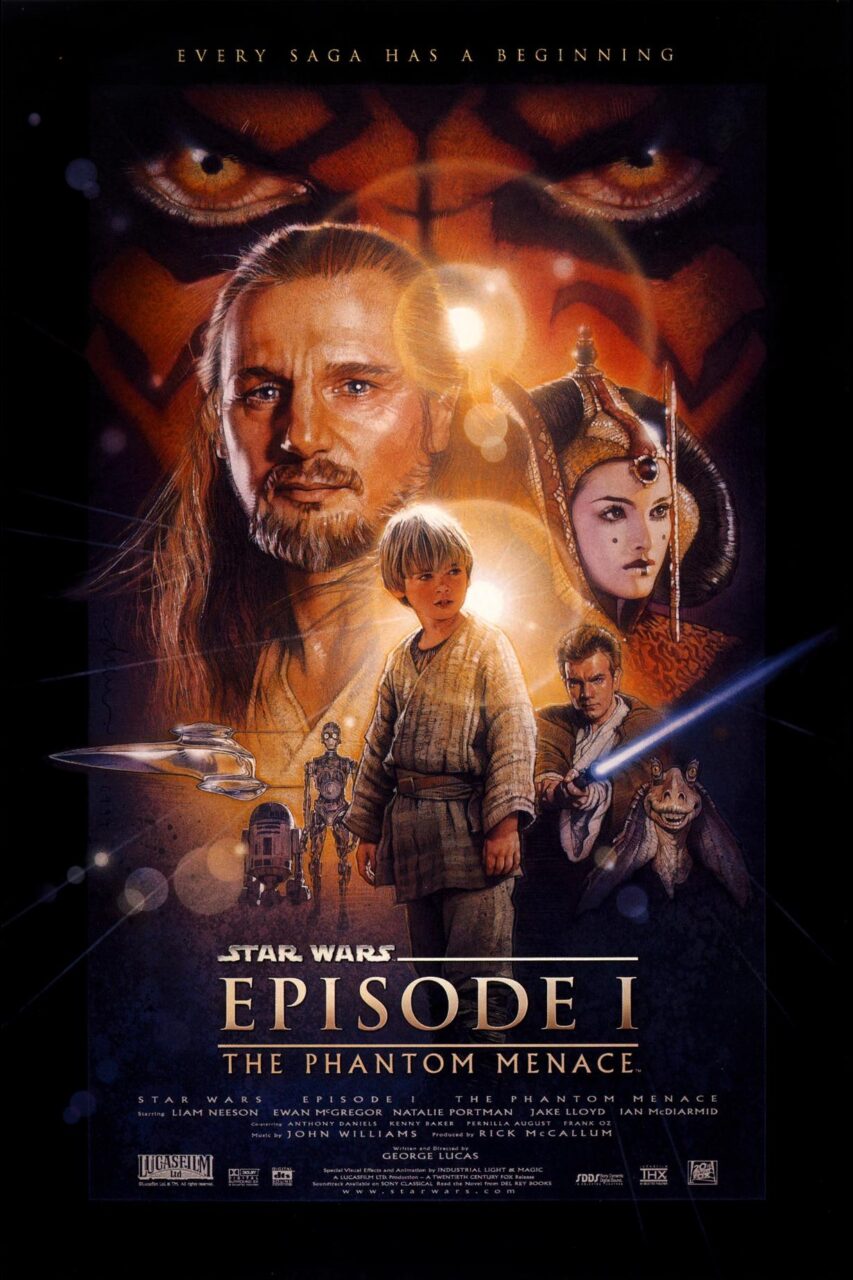

Cast

Liam Neeson (Qui-Gonn Jinn), Ewan McGregor (Obi-Wan Kenobi), Natalie Portman (Queen Amidala/Padme), Jake Lloyd (Anakin Skywalker), Ahmed Best (Jar-Jar Binks), Pernilla August (Shmi Skywalker), Ian McDiarmid (Senator Palpatine), Ray Park (Darth Maul), Brian Blessed (Boss Nass), Kenny Baker (R2D2), Hugh Quarshie (Captain Panaka), Frank Oz (Voice of Yoda), Samuel L. Jackson (Mace Windu), Anthony Daniels (Voice of C3P0), Terence Stamp (Chancellor Valorum)

Plot

The Galactic Republic dispatches two Jedi Knights, Qui-Gon Jinn and his apprentice, the young Obi-Wan Kenobi, to the peaceful planet of Naboo to negotiate an end to the blockade of vessels maintained by the Trade Federation in protest against galactic taxation. Their arrival panics the Trade Federation into invading Naboo with their droid armies. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan make an escape with Amidala, the young queen of Naboo. Damage to their ship causes them to put down on nearby Tattooine. In their search for repair parts, Qui-Gon encounters a young slave boy Anakin Skywalker who has an unprecedented command of The Force. Qui-Jon makes a bet on a pod race to free Anakin with the intention of taking him on as an apprentice. As they head on to the galactic capital Coruscant, it becomes clear that the invasion of Naboo is a feint for shadowy political machinations. Defying the Galactic Council’s desire for non-involvement, Qui-Jon and Obi-wan decide to liberate Naboo on their own. In doing so, they discover a powerful new menace in the Sith, a renegade faction of Jedi that have given themselves over to the dark side of The Force.

Star Wars (1977) came and went in the summer of 1977 and the phenomenon that accompanied it has gone on to become part of modern media mythology. Everything from the story of how George Lucas originally wanted to make a Flash Gordon movie and then went away and created his own saga when he found the rights were too expensive; to how the story was rejected by every studio in town, despite the runaway success of Lucas’s previous directorial outing American Graffiti (1973); to how Lucas had so little expectation of Star Wars being a success that he went away to Hawaii with his good pal Steven Spielberg (where the two of them cooked up the idea for a small adventure film called Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) on the beach); to how Star Wars took everybody by surprise and rocketed to the No. 1 box-office position overnight. It is mythology that is as much promulgated by the ensuing reclusiveness of George Lucas himself who made an abrupt retirement from the series at the very pinnacle of his achievement and handed the creative reins of the sequels over to other directors and screenwriters.

The success of Star Wars lay in its unalloyed evocation of a pure sense of gee whiz space opera wonderment that every science-fiction fan discovers about the age of fourteen. It dazzles with moments of dropjaw wonder – who can forget the opening moment where the battlecruiser rumbles across the screen, the excitement of the jump into hyperspace or the climactic Death Star attack. Star Wars is one of the few films that create a complete sense of a living breathing Otherworld. It is written to a simple black-and-white heroism that strikes a mythic universal chord. (Indeed, George Lucas claims to have crafted the saga from out of the universal myth templates of Joseph Campbell). The pleasures of Star Wars was maintained in the first sequel, the even superior The Empire Strikes Back (1980), which darkened the first film’s tone and deepened the characters while throwing in an absolutely exhilarating series of effects sequences. However, by the time of Return of the Jedi (1983), the series felt like it was on autopilot, the film little more than an extended toy commercial where the characters and enthusiasm of the first two films had been buried under effects sequences for their own sake and an unbelievably corny happy wrap-up ending of the saga.

Following Return of the Jedi, George Lucas’s original concept of a nine-episode saga in three trilogies was long believed to have been abandoned by all bar a few faithful fans who poured over every minute implication and backstory reference in the series looking for clues to the rest of the saga. As fans of Star Trek (1966-9) can attest, sometimes such faith can be rewarded. After sixteen years of waiting, there eventually came this prequel. To say that Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace was the most anticipated film of the decade, maybe even the century, may not be understatement – I doubt there is a single magazine or news programme anywhere that did not give coverage to it. Every scrap of detail – from the first photos to previews of the toys and the fights over who was the first person waiting in line to the first screening – resulted in a publicity feeding frenzy it would take the Second Coming to top.

It was an expedient time for George Lucas to return to the Star Wars series as it was needed for he to regain both his artistic and financial integrity. It may have escaped every loyal Star Wars enthusiast’s attention but outside of Star Wars George Lucas’s box-office record has been rather shaky. The Indiana Jones trilogy has been the only other success Lucas has had since the Star Wars films. All other Lucas films – the notorious Howard the Duck (1986), the underrated Labyrinth (1986), the sword and sorcery flop Willow (1988), Francis Ford Coppola’s Tucker: The Man and His Dream (1988), Radioland Murders (1994), Red Tails (2012) and Strange Magic (2015) – have been massive financial and, with the exception of Tucker, critical flops.

Throughout the 1990s, George Lucas’s sole source of revenue was the increasing pillaging of the Star Wars name in terms of merchandise. Film fans had been fed a starvation diet of the real thing with lame tv spinoffs like The Star Wars Holiday Special (1978), The Ewok Adventure/Caravan of Courage (1984) and Ewoks and the Marauders of Endor (1986) and the animated series’ Droids (1985-6) and Ewoks (1985-7). And then there was 1997’s re-release of the original trilogy, a monumental piece of oversell that restored a thirty-second scene cut from Star Wars and some digitally redressed backgrounds that added zilch and in many cases considerably distracted from the existing drama, while trying to sell the trilogy as new and improved.

On the bookshelves alone, Lucas launched several new series of books devoted to the original Star Wars characters, plus a series about the barroom exploits at the cantina Luke Skywalker briefly visits in Star Wars called Tales from the Mos Eisley Cantina and other spinoffs like Tales of the Bounty Hunters, Tales from Jabba’s Palace and X-Wing Squadron, all set in the same universe but with only the vaguest connection to the principal characters. Lucasfilm also published books of artwork, design schematics, cross-section illustrated books to the workings of the technology, Star Wars calendars and cookbooks, rebel entrance examinations and numerous encyclopedic guides to the worlds, characters and ships of not only the filmed adventures but their new and constantly expanding fictional universe.

This hit an almost surrealistic height with the release of Steve Perry’s exceedingly mediocre original novel Shadows of the Empire (1996). In addition to Shadows of the Empire artwork, Lucasfilm also released comic-book adaptions of the story, a tie-in computer game, a series of collectible trading cards, a soundtrack “inspired by the book”, a series of action figures of characters from the book and finally a Making Of book to document the phenomenon. And then there was the Lucasfilm’s Alien Chronicles series of books that would have you believe are based on well …. ideas that were floating around in the heads of some of the Lucasfilm staff (the series is unspecific as to whom), which were sold solely on the familiarity of the Lucas brand name attachment. That Star Wars fandom did not desert in droves after this commercial pillaging of their enthusiasm was a testament either to their endurance or their naivete.

With Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, George Lucas was clearly hoping that lightning would strike all over again. However, the milieu that The Phantom Menace entered into was a vastly different one to when Star Wars came out. Star Wars was a dark horse that nobody, not even its own creator, expected would be a success; The Phantom Menace was so heavily anticipated it was made in utmost secrecy with even its employees having to sign non-disclosure contracts and false scenes being filmed to mislead publicity hounds. The Phantom Menace came with a massive marketing tie-in where even the designs of the toys were a guarded secret and many US department stores sold out the first day items went on sale; Star Wars never even had a marketing tie-in until some months after the movie’s success when toymakers rushed to cash-in on the surprise phenomenon. For Star Wars, Industrial Light and Magic was formed in a disused warehouse, where a Commodore 64 used to track camera movements was considered a technical revolution in effects and where thirty seconds of simple computer animated line drawings in the Rebel briefing scene was considered the cutting edge of computer animation; The Phantom Menace comes made in a complete digital sound system designed by Lucasfilm and with entire characters and spaceship models that exist only inside a computer and where ILM has become the pre-eminent force in visual effects anywhere in the world. Not to mention that no film had done what Star Wars had done before, while The Phantom Menace has to compete against a hundred lesser imitators, even dozens of tv commercials, which have made the images of tiny ships conducting Immelman turns and firing laser beams, cute robots and Chris Foss-esque battlecruisers into overwrought cliches.

Of course, no film could ever hope to match up to the hype that surrounded The Phantom Menace. The question is whether one is able to critically distance themselves from not just the hype but also the backlash against the hype – the “May the Farce Be With You”-type reviews that some critics jumped in with irritably fashionable cynicism, sometimes even before the film opened. (My favourite in terms of hyperbole was the [Canadian] National Post, which reviewed The Phantom Menace alongside Tea with Mussolini (1999) and alikened the phenomenon to fascism).

On the plus side, The Phantom Menace is technically stunning. Unlike Return of the Jedi, which merely copied its effects set-pieces from the foregoing films, George Lucas has taken the sixteen years between episodes to think up some dazzling new ones. The pod race sequence – a combination of Death Star trench run and the chariot race from Ben Hur (1959) – is absolutely exhilarating, the show stopper that everybody came out talking about. So too is the marvelous climactic battle sequence between the Gungan and thousands of robot soldiers. Several of the characters – Jar-Jar Binks, a sort of combination of C3P0 and Roger Rabbit, and the Warta, a marvellously obscene flying bug – have been created entirely digitally.

Lucas also breathtakingly expands his vision of the Star Wars universe – underwater cities; a trip to the single city world of Coruscant (a direct steal from Isaac Asimov’s Trantor) and Naboo, which is a fantasticized version of Venice. If nothing else, George Lucas has set out to ensure that people would return to see the film more than once just to see everything that is going on in the background, which comes packed with so much in the way of detail, incidental action and throwaway creations that it is impossible to take in in one sitting.

Where The Phantom Menace does fall down, surprisingly enough for the fact that George Lucas has supposedly been planning the saga for more than twenty-five years, is the story. Some of it follows the same pattern as Star Wars – a young boy stuck on a nowhere desert planet coming to discover his mystical powers and the universe-changing destiny ahead of him; the independent minded queen/princess who needs rescuing; the young Jedi apprentice and his master who is tragically killed by a black-cloaked villain. As became the case in both The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, the plot tends to get conducted more in terms of effects set-pieces than story dynamics – the pod race sequence and the underwater journey through the planet’s core in a submersible serve no dramatic purpose other than to display effects work.

Moreover, the story does not feel complete. Star Wars may have been intended as part of a series but it had far more of a dramatic completeness than The Phantom Menace does. Too much of the story here is overshadowed by having to set the trilogy up for succeeding entries and character strands seem incomplete as a result. Anakin Skywalker’s story is clearly yet to come, although this is the best developed of them all. Liam Neeson has a quiet understated strength as Qui Gon-Jinn but as a character he is a virtual blank. The character of Darth Maul seems a woeful stab at the insertion of villainy into the story – he is literally a cliche black cloak villain – and lacks any of the power and shivery sense of evil that surrounded Darth Vader in the first trilogy. Natalie Portman is not bad as Padme but Ewan McGregor’s Obi-Wan Kenobi is relegated to no more than a series of kowtowing “Yes, Master”‘s throughout. The character scenes seem far too thinly interspersed between the effects and the adventure story. What The Phantom Menace badly lacks is characters at the centre of it. There is never anything of the sparring banter between the cocksure Harrison Ford and the brash Carrie Fisher, the aching youthfulness of a Mark Hamill or the serene genteel of Alec Guinness’s original Obi-Wan Kenobi.

The plot is full of irritating loose ends that should have been cleared up. It is never clear what the Phantom Menace of the title is meant to be. One supposes that it has to do with the plot’s political machinations – that the Menace is supposed to be the Trade Federation’s blockade and invasion of Naboo. What is going on is unclear – is the Trade Federation gambit a ploy to force Amidala to bring the no-confidence vote that allows Palpatine to succeed in council? Nothing is clearly spelt out. One senses that these answers will be made clear in Episode II, but it makes for incomplete and unsatisfying storytelling while watching the film. Similarly, the story has a subplot involving the friendship between young Anakin and Amidala’s decoy Padme (the surprise revelation about which that comes halfway through fools nobody in the audience) but never deigns to explain whether the person who befriends Anakin in the middle of the film is Amidala or Padme. These are obvious holes that could have been quickly patched over or clarified with little rewriting but are left irritatingly hanging.

In the end, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace is a mixture of pleasure and disappointment. It is the breath-taking array of technology and whiz-bang wonderment that every fan has wanted it to be and provides some of the most unalloyed excitement to be found on screen this summer. Underneath it however, the story remains moribund, too thinly spread around the effects set-pieces and in the end just not enough.

Next up in the series was Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) and Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005). These were then followed by the animated feature film Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008) and tv series Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008-14). In 2012, George Lucas sold Lucasfilm to Disney who produced a new trilogy of films with Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens (2015), Star Wars Episode VIII: The Last Jedi (2017) and Star Wars Episode IX: Rise of the Skywalker (2019). Disney also created a series of live-action spinoff films with Rogue One (2016) and Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018), plus the tv series’ The Mandalorian (2019- ), The Book of Boba Fett (2021-2), Andor (2022- ), Obi-wan Kenobi (2022), Ahsoka (2023- ) and The Acolyte (2024). Also of amusing interest is Fanboys (2008) about a group of Star Wars fans that go on a road journey to break into the Skywalker Ranch and see a work print of The Phantom Menace, while the documentary The People vs. George Lucas (2011) discusses the failings of and the fan disappointment with The Phantom Menace. In 2012, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace was re-released in 3D.

(Winner for Best Special Effects and Best Production Design, Nominee for Best Musical Score at this site’s Best of 1999 Awards. No. 1 on the SF, Horror & Fantasy Box-Office Top 10 of 1999 list).

Trailer here