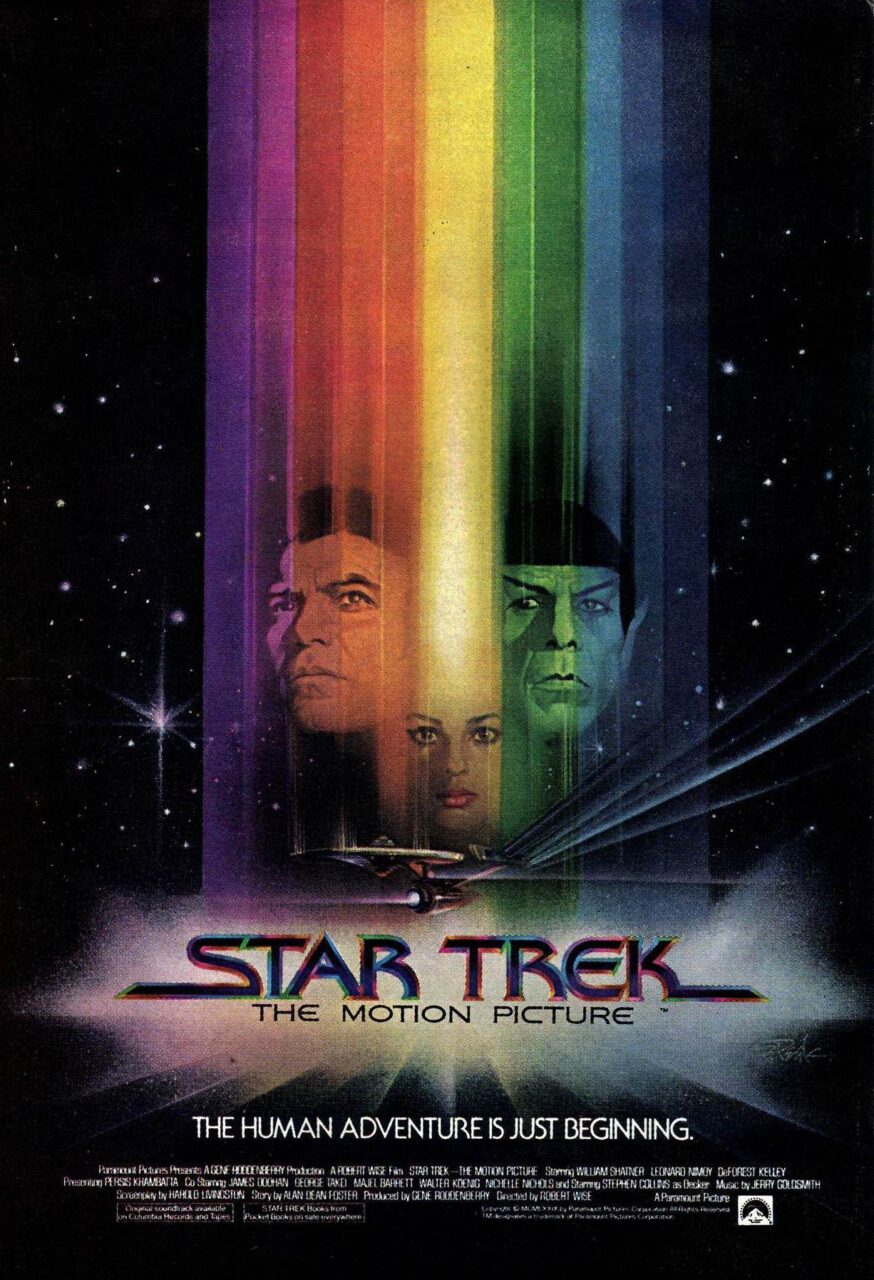

USA. 1979.

Crew

Director – Robert Wise, Screenplay – Harold Livingston, Story – Alan Dean Foster, Producer – Gene Roddenberry, Photography – Richard H. Kline, Music – Jerry Goldsmith, Photographic Effects Supervisors – John Dykstra & Douglas Trumbull, Miniatures – Grant McCune, Animation Effects – Robert Swarthe, Special Effects Supervisor – Joe Weldon, Mechanical Effects – Mary Bresin, Ray Mattey & Darrell Pritchett, Makeup – Ve Neill & Fred & Janna Phillips, Production Design – Harold Michelson, Technical Advisors – Isaac Asimov & Jesco von Puttkamer. Production Company – Paramount.

Cast

William Shatner (Admiral James T. Kirk), Leonard Nimoy (Spock), DeForest Kelley (Dr McCoy), Stephen Collins (Captain Willard Decker), Persis Khambatta (Lieutenant Ilia), James Doohan (Commander Scott), George Takei (Commander Sulu), Nichelle Nichols (Commander Uhura), Walter Koenig (Commander Chekov), Majel Barrett (Dr Christine Chapel), Grace Lee Whitney (Lieutenant Janice Rand), Mark Lenard (Klingon Captain)

Plot

A giant hydrogen cloud heads towards Earth, destroying everything in its path. James Kirk, now a ground-based admiral in Starfleet, uses the opportunity to take command of the newly refurbished Enterprise, pushing aside its new captain Willard Decker. Reuniting his old crew, he heads out to intercept the cloud. Penetrating the cloud, they find a vessel of unimaginable size and power.

It is hard to pinpoint the exact reason for the phenomenon that became Star Trek. The original tv series ran for 79 episodes in three seasons between September 1966 and June 1969. Star Trek was immediately different to any science-fiction series that had appeared on tv before. While it is fashionable to denigrate Star Trek in some circles, a strong argument could be made that Star Trek is the fulcrum that took media science-fiction away from alien invasion stories of the 1950s and televised space opera like Lost in Space (1965-8) and gave it a thinking edge.

The creative mind behind Star Trek was Gene Roddenberry (1921-99). Roddenberry’s ability was less one as a writer – the half-dozen scripts he turned out for the series are some of its most heavy-handedly polemical (including The Omega Glory where The Enterprise encounters a planet where the Yangs and Koms fight and the day is won by Captain Kirk’s recitation of the Declaration of Independence, and The Savage Curtain where Abraham Lincoln is revived for hand-to-hand combat on an alien planet). Gene Roddenberry’s real ability was in reigning in some of the era’s finest literary science-fiction writers – including the likes of Norman Spinrad, Theodore Sturgeon, Harlan Ellison, Robert Bloch, even the dubious merit of giving David Gerrold his first writing credit.

Star Trek is sometimes overblown but it is thinking science-fiction. Roddenberry’s stories defused the armed standoff with the rest of the universe that had been the legacy of the Cold War and 1950s science-fiction and showed that sometimes the face of the enemy was clouded by human prejudice. In Star Trek, monsters and threatening aliens would be revealed to be simply an alien mother protecting her eggs or a lonely child.

At its worst, Star Trek gave us the Society of the Week syndrome – an intergalactic variation of Manifest Destiny wherein the American Way was held up to be the best of all possible societies and a cardboard alien society (various ones where children rule, women rule, where computers run people’s lives etc) was held up by each particular episode and then demolished by the brash Captain Kirk. This was a model that rapidly became the dominant paradigm for US science-fiction television in the likes of Starlost (1973), Planet of the Apes (1974), Logan’s Run (1977-8) and Sliders (1995-2000). Some of the societies of the week that turned up in Star Trek started to get thinly stretched – toward the final season, we were getting episodes where aliens and sociologists recreate the Third Reich, Prohibition Chicago, the Roman Empire and the Gunfight at the OK Corral in outer space because reusing studio costumes and sets was a cheap way to go on location to another planet.

However, the real life of Star Trek had less to do with its politics than it does its fandom. When NBC threatened to drop the series at the end of the second season, fans sparked up a one million plus letter writing campaign. Following the cancellation of the series in 1969, the conventions sprang up and have been going ever since with no sign of letting up. Star Trek fandom, rather than existing around any genuine appreciation of the series science-fiction content, is more what one might call a personality cult, centring as it does around the series central triptych of characters – the wily Captain Kirk, the grizzled Dr McCoy and especially the stoic half-human, half-Vulcan Mr Spock who has become the focus of an enormous amount of erotic fiction. From the mid-1970s onwards, Star Trek has become a major publishing industry in terms of original fiction, something that is now threatening to completely overrun the science-fiction shelves in bookstores.

The fandom spurred a two season animated revival of the series in 1972 with most of the cast returning to voice their roles – but that was not enough for fans who wanted the real thing. The series’ return was something that debated for a number of years – it became less a question of whether Star Trek would than one of what form it would take. Philip Kaufman, the director of the remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) and The Right Stuff (1983), was aboard the project for a time, turning out an interesting sounding script for a feature film that focused on Spock’s emotional side.

However, the Star Trek revival had to wait for the success of Star Wars (1977) to give legitimacy to the idea of big-screen science-fiction. After Star Wars went big, the Star Trek revival became a hot ticket. For more than two years between 1977 and 1979, Paramount flip-flopped every second week as to whether it would be a big-screen revival or a new tv series Star Trek II or whether Leonard Nimoy would return (he withheld from signing back on due a lawsuit he had launched against Paramount for the use of his likeness without paying royalties. At one point, the role had been recast with David Gautreaux as Xon, a different Vulcan science officer. Gautrexu who has a minor cameo in the film as the crewmember who dies in a transporter accident). There was such a buzz that magazines like Starlog had monthly columns from Gene Roddenberry’s secretary that reported every detail of the latest development. The anticipation developed such a head of steam that when Star Trek – The Motion Picture opened, it seemed like an epic.

Robert Wise, the Academy Award-winning director of films like West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965) and genre classics such as The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), The Haunting (1963) and The Andromeda Strain (1971) was brought in to helm the film. (See below for Robert Wise’s other films). With a $47.5 million budget, Star Trek – The Motion Picture was the most expensive film ever made at the time.

However, when it finally appeared on screen, Star Trek – The Motion Picture disappointed most of the series’ fans and critics alike – earning Star Trek – The Motionless Picture and Spockalypse Now-type reviews. Part of the problem had been a surfeit of cooks in the broth behind the scenes. People seemed uncertain about what was happening, while the script was being rewritten even the same day as scenes were being shot. (Harlan Ellison tells an amusing story about pitching a script to Paramount who demanded something epic – he offered a story in which The Enterprise passed outside of space/time and saw the eye of God looking back at them, only to be told that they wanted something bigger).

The story the film does end up with (which was originally written for Gene Roddenberry’s failed Genesis II post-holocaust tv series) seems to have been cobbled together from various Star Trek episodes – notably The Changeling (1967) about a misguided machine seeking its creator, and the animated episode One of Our Planets is Missing (1973) about The Enterprise journeying into the gut of a giant sentient cloud organism. Unfortunately the film’s denouement – that the vast machine is an ancient NASA probe that has been transformed into an AI junkpile that can create androids with molecular-sized micro-processors but is unable to scrape dirt off its own central unit and read its name – seems like a giant shaggy dog story that falls flat at the punchline.

What emerged seemed an epical monument to empty-headed post-Star Wars madness. Star Trek – The Motion Picture appears a hugely self-indulgent mess – for instance, six million dollars of the budget was spent on developing special effects with Robert Abel and Associates without a shot ever being put on film before Paramount decided to fire them. Much was also spent on a large number of alien creations that featured heavily in the publicity, only a handful of which ever appear on screen and in brief background shots. As most of the film takes place on the Enterprise bridge, it is hard to see where the other forty odd million went, except in bureaucratic muddling. (According to Robert Wise, who says this was not his favourite directing experience, a large part of the problem was that the script was continually being rewritten, sometimes multiple times a day, and right up until the last day of shooting).

Furthermore, there is not a good deal of the spirit of the original series in the movie. What seemed comfortably cosy on the small-screen has been drowned out on the big screen by Messrs Trumbull and Dykstra. The only characters that return with any success are William Shatner’s Captain Kirk and DeForest Kelley’s Dr McCoy who, as always, gets the best lines. Leonard Nimoy seems strangely aloof from proceedings and the others are, as usual, relegated to the background. The newcomers are disappointing – Indian actress Persis Khambatta cuts a strikingly sexy figure in shaven head and mini-skirts but displays no noticeable difference between when she is flesh and blood and an emotionless android.

On the other hand, while it is not great Star Trek, Star Trek – The Motion Picture is not too bad a science-fiction film at all. The unfolding mystery as The Enterprise journeys inside the cloud is superb – here the film holds a growing sense of the spectacularly awesome, of heading toward a meeting with something genuinely alien and almost incomprehensibly immense. The effects are remarkable – like the stunning tour of the brand new Enterprise in space-dock, and the fantastically alien conception of the interior of the cloud all in beautiful cold light and incomprehensible promethean machinery so big that even pullbacks showing the Enterprise the size of a pinhead cannot demonstrate its full size.

Star Trek – The Motion Picture is one of the few films to come near approximating the sense of awe that 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) does. While the subsequent film sequels fell into a cosy middle-age after the creative control was taken over by the cast, Star Trek – The Motion Picture is the only classic Star Trek film to contain a sense of boldly adventuring rather than being a snug character reunion and half-hearted galactic adventure.

Jerry Goldsmith creates a superbly eerie and guttural score. And the costume and set designs are excellent. As Star Trek, Star Trek – The Motion Picture is not a success but then as science-fiction it is by no means a failure either.

The Director’s Cut was released in 2001 and a 4K restoration in 2022. A good deal of effort and cost was placed into fixing this. This includes adding new visual effects shots – the most notable of these being the replacement of the statues on Vulcan and V’Ger’s arrival in orbit around Earth. At the same time, some of the existing effects scenes have been trimmed down for purposes of pace such as Captain Kirk’s lengthy tour of the refurbished Enterprise and the journey into the V’Ger cloud. There is not a substantially new amount of material – just expansions of the odd line of dialogue in a few scenes, including seeing Spock weep for V’Ger and a scene where Ilia heals a wounded Chekov.

The other Classic Star Trek films are:- Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984), The Voyage Home: Star Trek IV (1986), Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989) and Star VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991). Star Trek was revived in four new series in the 1980s and 2000s – Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94), Star Trek: Deep Space Nine (1993-9), Star Trek: Voyager (1995-2001) and Enterprise (2001-5). Star Trek: The Next Generation became as popular as the original series and ran even longer, eventually creating a new generation of fans who regarded it as the legitimate Star Trek and the original series as dated. Star Trek: Generations (1994), Star Trek: First Contact (1996), Star Trek: Insurrection (1998) and Star Trek: Nemesis (2002) are film spinoffs from The Next Generation. The original series was cinematically revived by J.J. Abrams as Star Trek (2009), which recast the classic series with new faces and told an origin story, and was followed by Star Trek: Into Darkness (2013) and Star Trek: Beyond (2016). The third generation revival tv series are Star Trek: Discovery (2017-24), Star Trek: Picard (2020-23), the animated Star Trek: Lower Decks (2020- ), Star Trek: Prodigy (2021- ) and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds (2022- ). Star Trek: Section 31 (2025) was a film spinoff from the revival series. Also of interest are Trekkies (1997) and Trekkies 2 (2004), two documentaries about Trek fandom; Free Enterprise (1998), an excellent fictional film about fans; GalaxyQuest (1999), a witty parody of both Star Trek and its fandom; and William Shatner’s documentary The Captains (2011) about the actors who played the captains in the various series.

Robert Wise was a classic director who made a number of celebrated films in a number of genres, including Run Silent, Run Deep (1958), West Side Story (1961) and The Sound of Music (1965). Wise’s other genre films are:– The Curse of the Cat People (1944) and The Body Snatcher (1945), two classic psychological horror films made for Val Lewton; the human hunting film A Game of Death (1945); the science-fiction classic The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951); the haunted house classic The Haunting (1963); the Michael Crichton adaptation The Andromeda Strain (1971); and Audrey Rose (1977), a courtroom drama about reincarnation.

Trailer here