(Suchîmuboi)

Japan. 2004.

Crew

Director – Katsuhiro Otomo, Screenplay – Katsuhiro Otomo & Sadayuki Murai, Producers – Shinji Komori & Hideyuki Tomioka, Music – Steve Jablonsky, Production Design – Shinji Kimura. Production Company – Steamboy Committee.

Plot

Manchester, England, 1866. Schoolboy James Ray Steam is an amateur inventor who makes various mechanical and steam-powered devices out of scavenged materials, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfathers who were both steam-technology engineers. Ray then receives a parcel from his father that contains a sphere. Immediately after, two sinister men from the O’Hara Foundation, his father’s employers, arrive wanting the sphere back. The letter in the parcel warns that Ray must not give them the sphere and he flees. He is captured and meets his father, believed dead but now rebuilt with mechanical parts. His father wants to use the sphere, which is capable of compressing steam to an unknown new degree and releasing vast power, to complete construction of a vast steam palace that he says is the way of the future, while the Foundation want to build powerful new weaponry for sale to the highest bidder. At the same time, the forces of the British Empire want to commandeer the sphere to make the British Armed Forces stronger. Ray is caught between the two sides as they unleash their steam-powered weaponry against one another in a vast battle in the centre of London.

Katsuhiro Otomo is without any question one of the grandmasters of modern anime. The one film that Katsuhiro Otomo’s reputation rests on is Akira (1988), which he directed and wrote based on a manga that he had earlier created. Akira created stunning vistas of mass destruction, while its breathtaking contrasts of huge and tiny scale has been a strong influence on much of modern anime, not to mention the fact that the film popularised the cult of anime in the West. Many films have followed Akira but none have managed to create a sense of the epic scale as well as Katsuhiro Otomo did.

Alas, one of the people who have failed to capitalise on Akira was Katsuhiro Otomo himself. In the seventeen years between Akira and Steamboy, Katsuhiro Otomo made one-and-a-third other films – the live-action horror film World Apartment Horror (1991) and a segment of the anime anthology Memories (1995). Otomo’s name has been attached to a number of other anime in various regards – he started production on Roujin Z (1991) but departed; wrote Rintaro’s Metropolis (2001); and has had all sorts of nebulous titles like ‘special adviser’ and ‘general supervisor’ on Perfect Blue (1997) and Spriggan (1998). Steamboy was Katsuhiro Otomo’s first fully-fledged return to animation as director since Akira. Steamboy took ten years to make and with a $22 million budget was the most expensive anime ever made.

While Katsuhiro Otomo ventured into Cyberpunk futures and extraordinary visions of mass destruction in Akira, Steamboy travels in completely the opposite direction and is a vision of a mass destruction set in a retro world. Here Katsuhiro Otomo ventures into the genre of Steampunk, a thematic subgenre within literary science fiction that emerged in the mid-1990s. As Cyberpunk had done, projecting imagined futures based on the burgeoning computer technologies of the 1980s, Steampunk likewise projected backwards to derive an imagined world based on the technology of the late 19th Century following the Industrial Revolution and just prior to the advent of electricity. Steampunk created a world that seemed like a future imagined by Victorian engineers – all steam and whirring clockwork technology, bolted boilerplates and brass fittings and peopled by elegant English aristocracy and Dickensian street urchins.

The progenitors of Steampunk were literary works such as Harry Harrison’s A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! (1972), Michael Moorcock’s Oswald Bastable series and K.W. Jeter’s Morlock Nights (1979). Since then the genre has grown with a number of writers such as Jeter, James Blaylock and China Mieville regularly working within it, even a variety of role-playing games such as Space: 1889 and GURPS Steampunk and the popularity of the League of Extraordinary Gentlemen graphic novels.

One of the unacknowledged sources of the Steampunk genre was actually the fad for Jules Verne and H.G. Wells film adaptations during the 1950s/60s with the likes of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), The Time Machine (1960), Master of the World (1961), The First Men in the Moon (1964) and in particular The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (1958), which begat the Victorian retro-technology look long before the literary genre came along. There have been minor sporadic appearances of Steampunk technology before in films like Young Sherlock Holmes (1985) and Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001) and tv’s The Secret Adventures of Jules Verne (1999-2000). Although there has been a surprising preponderance of Wild West Steampunk adventures on film – a genre that has never taken off on the literary page – with the likes of tv series such as The Wild, Wild West (1965-9), The Adventures of Brisco County, Jr. (1993) and Legend (1995) and the film Back to the Future Part III (1990).

The nearest point of comparison between what Katsuhiro Otomo does with Steamboy might be with William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s collaboration on the novel The Difference Engine (1990), which has become one of the acknowledged classics of literary Steampunk. Gibson and Sterling were both the leading voices of Cyberpunk fiction and felt that in order to further their implied social critique the logical place to go was to extend their milieu backwards and create a similar vision using retro-Victorian technology. In similar ways, Steamboy is Akira having been extended backwards – it is the same vision of mass destruction and a similar story taken from a Cyberpunk future and translated to a retro-Victorian milieu.

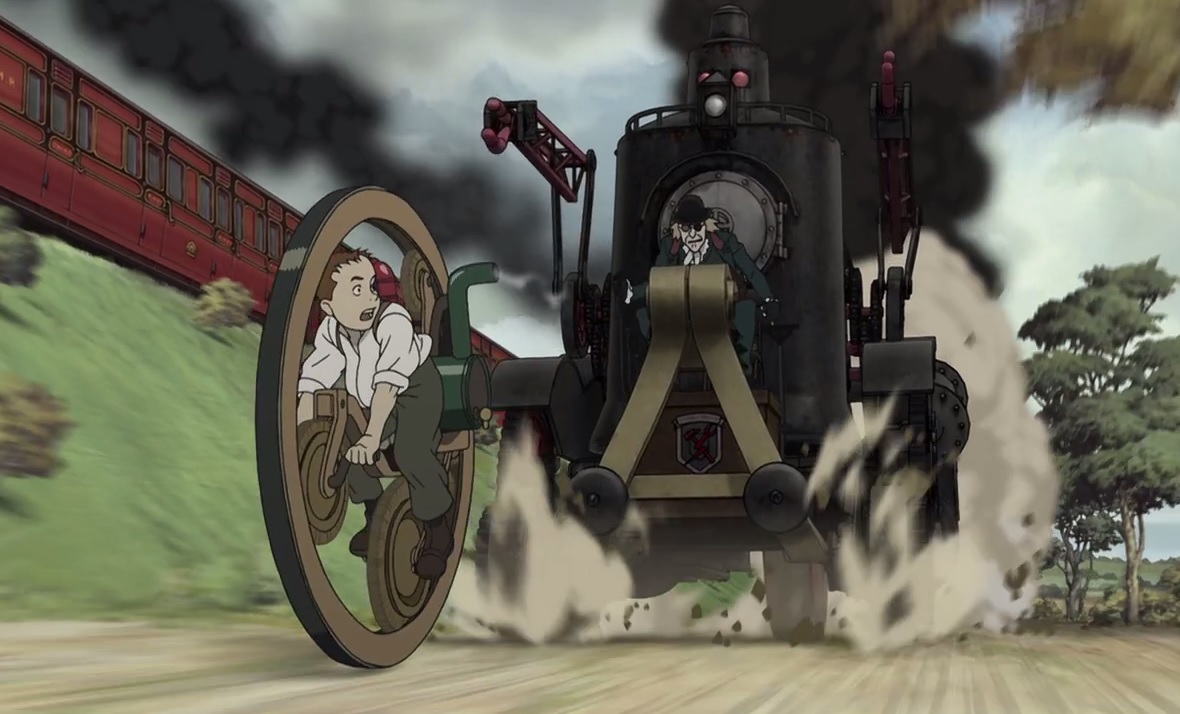

Expectedly, Katsuhiro Otomo creates a visually stunning film with Steamboy. He and his designers apparently spent some months in the UK studying the architecture and technology at various museums. There is an authenticity to the film with faithful recreations of the buildings of Victorian London – The Crystal Palace, St Paul’s, London Bridge and the halls of the London Expo. Steamboy allows Katsuhiro Otomo to do what Otomo does like no other – creating animated vistas of mass destruction. There are some dazzling early sequences, particularly with Ray riding his steam monocycle and pursued up onto the railway tracks by a steam tractor and the glorious vision of a dirigible coming down to snatch the carriage up into the air.

Katsuhiro Otomo is in his element in the second half of the film where he creates incredible visions of battleships along the Thames, rickety steam-powered flying machines and backpacks, battalions of armoured steam soldiers and the stunning images of the giant steam-powered battle palace rising up over the city of London and crushing buildings beneath its feet. Not to mention images of often hauntingly poetic beauty like the dome of a crystal palace shattering into thousands of tiny shards as it topples or of a dirigible surreally frozen inside a wave of ice.

The extended climactic sequence does perhaps go on a little too long – the American English-language dubbed version removes some fifteen minutes of running time from these sequences – nevertheless, Steamboy is a Katsuhiro Otomo film and does exactly what Katsuhiro Otomo does best – offer up mass-destruction on a truly epic, mind-boggling scale.

While Steamboy is in many ways the apocalyptic vision of mass destruction that we saw in Akira translated into retro-Victoriana, the one noticeable thing is that Katsuhiro Otomo takes a strong moral position on all the devastation. Akira seemed to offer up all the mass destruction without any particular moral viewpoint, excepting perhaps that of seeing it all arrayed for viewer pleasure. On the other hand, Steamboy asks questions about the moral rightness of the technology on display. On one hand, Otomo gives us the military-industrial complex and their viewing of the technology of mass destruction as grist for profit making. Here Otomo sees that the vision that glorifies technological progress is only one that masks an inevitable ruthless capitalist exploitation.

On the other hand, we see the British Empire who have a more noble purpose in mind but are ultimately seen as wanting to appropriate the weaponry for the purposes of nationalistic might. Otomo roundly criticises either side and the whole film is about a struggle to find a morally right purpose for the application of the technology. Perhaps in the end, the scenes where the arms are demonstrated to foreign bidders and the hero’s struggle for an individualistic moral position does seem informed more by 20th Century attitudes that 19th Century ones. And it is certainly a very Japanese moral position – a British version of the story would almost certainly have sided with the rightness of the Empire in these matters, but having been made in an ardently pacifist and demilitarised country like Japan the very idea of national military power is strongly decried.

Following Steamboy, Katsuhiro Otomo next went onto make Bugmaster (2006), a live-action film about a wandering exorcist and the Combustible episode of the anime anthology Short Peace (2013).

Trailer here