UK. 1936.

Crew

Director – William Cameron Menzies, Screenplay – H.G. Wells, Producer – Alexander Korda, Photography (b&w) – Georges Perinal, Music – Arthur Bliss, Special Effects – Ned Mann, Production Design – Vincent Korda & Moholy Nagy. Production Company – London Films.

Cast

Raymond Massey (John Cabal/Oswald Cabal), Edward Chapman (Passworthy/Raymond Passworthy), Margaretta Scott (Roxana Black/Rowena Cabal), Ralph Richardson (Rudolph, The Boss), Cedric Hardwicke (Thetocopolous), Maurice Braddell (Dr Harding), Sophie Stewart (Mrs John Cabal), Derek De Marney (Richard Gordon), Ann Todd (Mary Gordon), Pearl Argyle (Catherine Cabal), Pickles Livingston (Horrie Passworthy)

Plot

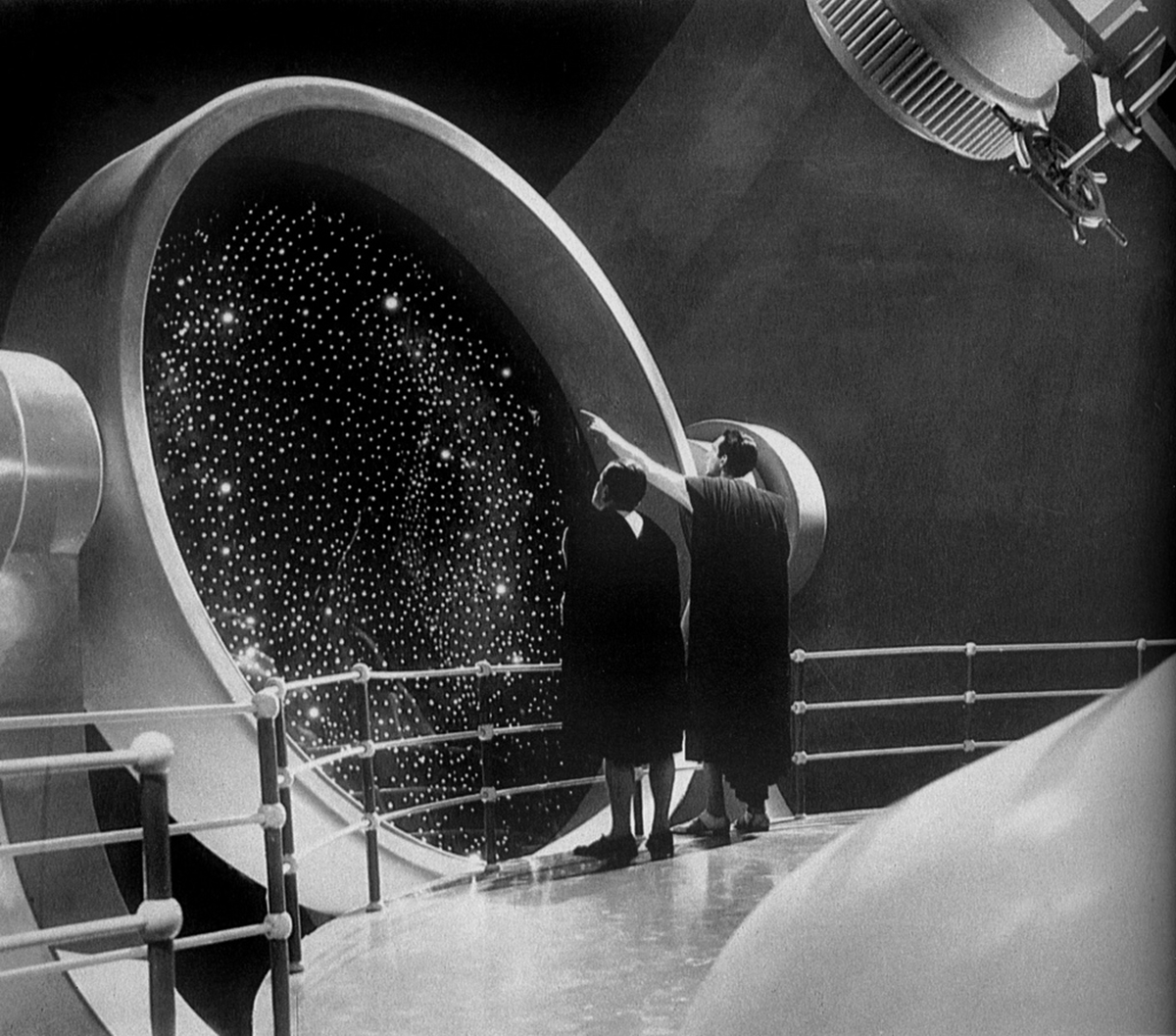

On the Christmas Eve of 1940, war begins as the city of Everytown is bombed. The war lasts 66 years, during which time civilisation falls into anarchy. Eventually the warlord who calls himself The Boss emerges to establish brutish control over the chaos. However, a scientific group called Wings Over the World emerges and is able to quash the regime of The Boss using a peace gas. The scientists then set about building a shining white new scientific Utopia on the ruins of the old civilisation. In the year 2036, the culmination of the new society’s scientific vision is the launching of the first Moon shot.

H.G. Wells (1866-1946) is one of the founding fathers of modern science fiction. The peak of H.G. Wells’s success, at least as a science-fiction author, was during the first decade of his publishing career, 1895 to the early 1900s. During this time, Wells published major works and laid down what are today still some of science-fiction’s major thematic preoccupations – The Time Machine (1895), which created the idea of the time machine and set in place much of the time travel story; The Island of Dr Moreau (1896), which, even though it did not name such, laid down many of the themes of the modern genetic engineering story; The Invisible Man (1897), the first invisible man story; The War of the Worlds (1898), the first alien invasion story; and When the Sleeper Awakes (1899), the first story in which a cryogenic sleeper awakes to encounter a future society.

What many readers who come to H.G. Wells through his science-fiction do not realise is that after around 1905, H.G. Wells fairly much abandoned the scientific romances that made his name and are his most popular works. Wells’s output of the decade ahead began to move towards serious fiction – works like Love and Mr Lewisham (1900), Kipps (1905), Tono-Bungay (1909) and The History of Mr Polly (1910) – as Wells attempted to establish himself as a serious novelist. For the bulk of the rest of his career up until his death in 1946, Wells became an ideologue. During this time, Wells began to write essays on futurology and dedicated himself to finding a means of improving the world through scientific progress. Wells also became an ardent member of the Fabian Society, an earnest group of socialists who were determined to bring about social change.

During the 1920s, 30s and 40s, H.G. Wells had become so famous that he even achieved the position of elder statesman and toured the world, lecturing and meeting with world leaders in an attempt to impart his views. The coming of World War I proved a fundamental changing point for Wells. He initially supported the War in the hopes that this would bring about the social changes he ardently wished for, but soon became deeply disenchanted – after this point, a disillusioned pacifist tone enters his work. He continued to write science-fiction up until his death but all of this is tainted by heavy-handed message-making.

By the time of The Shape of Things to Come (1933), the book that this film is nominally based on, his scientific romance had become dry speculative sociological tracts. It is the same in other works like The Undying Fire (1919), the Book of Job is rewritten as an ideological treatise set in Wartime England, while in Mr Blettsworthy on Rampole Island (1928), a Robinson Crusoe figure tries to show reason to ignorant natives only to eventually find that he is in New York City. Today much of H.G. Wells’s science-fiction of this era is dated, heavy-handed and often idealistically naive. It is ironically only for his earlier scientific romances that H.G. Wells is remembered, even though he dismissed them for their unseriousness in later years.

H.G. Wells only saw his work adapted to screens a handful of times during his lifetime. The First Men in the Moon (1901) was uncreditedly stolen by Georgez Melies in A Trip to the Moon (1902) and then given a sanctioned adaptation in the lost The First Men in the Moon (1919). Hollywood caught onto H.G. Wells in the 1930s with adaptations such as The Island of Lost Souls (1932), from The Island of Dr Moreau, and The Invisible Man (1933).

H.G. Wells disparaged both of these for their light treatment, in particular The Island of Lost Souls for turning the material into a horror film, although it is useful to remember that Wells was heavily into his ideologue phase by then and had renounced his earlier works. In actuality, both of these films rank as two of the best H.G. Wells screen adaptations. Wells himself had earlier broached film work with a script he had written in 1929 called The King Who Was a King, wherein a king institutes socialist reform and this catches on worldwide, but this had been rejected as unfilmable. Wells then paired with Hungarian-born movie mogul Alexander Korda for two films – Things to Come, which was loosely adapted from The Shape of Things to Come, and the lighter (albeit still message-heavy) The Man Who Could Work Miracles (1937).

Producer Alexander Korda was a Hungarian immigrant to England and a former film critic. As a producer, Alexander Korda was one of the genuine movie moguls of the 1930s and 40s. He produced the likes of The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933), The Scarlet Pimpernel (1934), Sanders of the River (1935), The Ghost Goes West (1936) and later works like Rembrandt (1936), I, Claudius (1937), The Four Feathers (1939), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), That Hamilton Woman (1941), Jungle Book (1942) and To Be or Not to Be (1942).

For Things to Come, Korda handed the directorial reins over to William Cameron Menzies. William Cameron Menzies had been an art director and production designer on various films of the silent era and made his directorial debut with the lost Always Goodbye (1931). From there, William Cameron Menzies went onto a strong genre association with the likes of Chandu the Magician (1932), adapted from the radio series about a mystical superhero; the Communist fifth column thriller The Whip Hand (1951); the classic alien invasion and takeover film Invaders from Mars (1953); and the very peculiar The Maze (1953).

Things to Come is the essence of what H.G. Wells railed against and beat his tub about in later life. It loudly decries the futility of war. [Wells is uncannily predictive of the coming of World War II, seeing it as starting in Christmas 1940 (whereas the real one began in September 3, 1939), although is slightly less accurate in saying that it would last 66 years]. The middle of the film pours contempt on the petty-mindedness of self-interested classes and regards scientists as an intellectual elite, something that H.G. Wells himself did. The final third of Things to Come concerns the literal building of a scientifically-based utopia in clean, shining perfection, the pure world that Wells naively hoped would come and sweep away the rubble of the petty squabbling imperialist present.

The final speech that the film goes out on – “All the universe or nothingness? Which shall it be, Passworthy, which shall it be?” – is one of the most visionary speeches in all of science-fiction cinema – the view that now armed with scientific reason and determination the whole of the universe can be humanity’s for the conquering. It is certainly remarkable to compare the visions of scientific reach offered by Things to Come, which was made in England, and those offered by Frankenstein (1931) and the body of mad scientist films that were being made around the same time in the US. Where H.G. Wells believed the whole of the universe could be humanity’s for the conquering if only we were able to sweep away the imperialist, warlike past; Frankenstein et al are films that are deeply afraid of such scientific vision – the American equivalents see the desire to claim the whole of the universe as doom-laden and likely to cause social chaos. If Things to Come were made in Hollywood at the same time, almost certainly the scientists from Wings Over the World would have been the ones that inadvertently caused the war, while Thetocopolous’s and the masses storming of the rocket launch would have been regarded as a triumphal act.

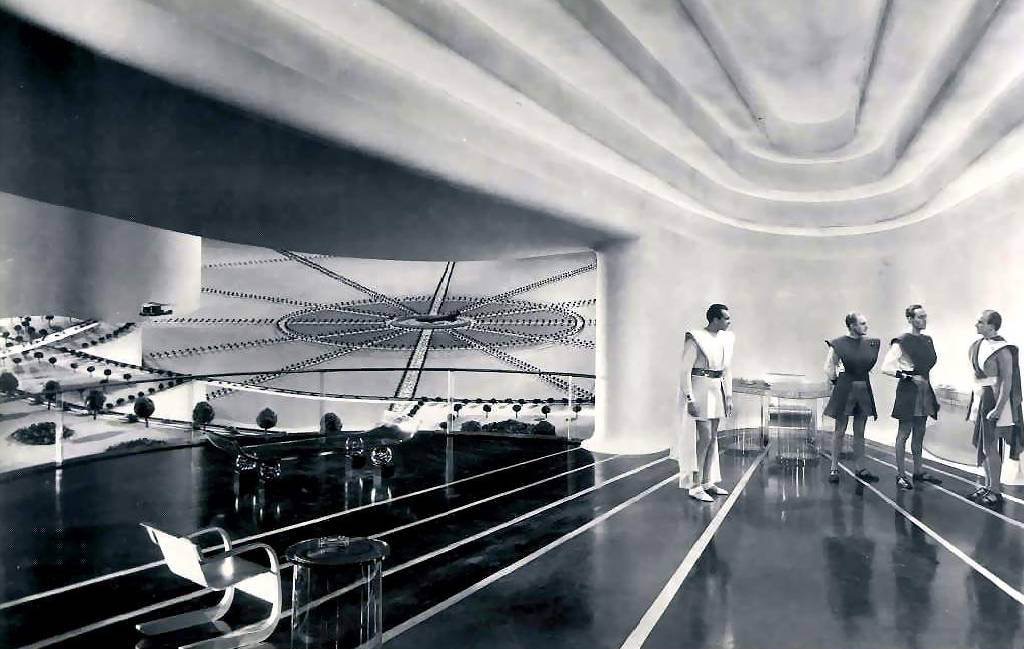

The only point of comparison with other films up unto that point had been Fritz Lang’s silent classic Metropolis (1927). H.G. Wells hated Metropolis and his express instructions to the production team were that they create exactly the opposite of Metropolis. Both are films that offer amazing visions of cities of the future and human scientific progress; both are ideologically concerned about the social failings of the present and envision the creation of a new Utopian society that would set these wrongs aright.

In Metropolis, Fritz Lang and his co-writer wife Thea von Harbou were very much caught up in a classically Marxist vision of the wealthy industry owners exploiting the unskilled masses; H.G. Wells, who came from a middle-class background, has no real interest in the exploited masses, rather his is the vision of the devastating effects that war has on the human race. While both films regard the self-interested plutocrats – Gustav Froelich’s Freder in Metropolis and Ralph Richardson’s The Boss here – as the villains, the view of either film toward progress is almost entirely reversed – Lang saw machinery, technology and progress in hysterical terms of Biblical enslavement, while his scientist was a madman akin to an alchemist. (Naturally, you can understand why Wells hated Metropolis).

On the other hand, Things to Come regards technology (and by implication industry) as having an almost transcendentally liberating effect. The concept that worried Lang and von Harbou of there having to be a necessary unskilled working class to build the shining city of the future is something that never dawns upon the horizon of H.G. Wells’s conception; in his society there are apparently no labour classes. Although interestingly, Wells’s earlier novel The Time Machine (1895), with its vision of a far-flung future where humanity has devolved into two species, the idyllic Eloi and the cannibalistic underground-dwelling Morlocks, representing a dim memory of class divisions, comes closer to Metropolis than Things to Come does.

Things to Come is undeniably a landmark science-fiction film. It always ends up on the list of genre classics. As a film, Things to Come is a peculiar mix of the pompous and boring and the genuinely visionary. William Cameron Menzies is not particularly well skilled at directing actors and his forte, also seen in later films like Invaders from Mars, comes in the sets and his actualisation of Wells’s Utopia. Things to Come is a film where one gets the impression that Alexander Korda was too much in awe of H.G. Wells and allowed his vision too much creative control to the point that what ended up being created is a static world devoid of much in the way of dramatic interest.

The film certainly has a wild visionary giddiness – the scenes of the rebuilding of the Everytown as a shining white scientific wonder city of the future have an outlook that sends a thrill of excitement. In all other ways though, Things to Come is a turgid polemic diatribe and a ponderous bore. Characters are always looking up at the heavens and uttering pompously noble epithets on the state of mankind/the wonders of science/the evils of war. H.G. Wells seems incapable of writing ordinary people, ones that are not mouthpieces constantly iterating some point of view.

Lumbered with this kind of dialogue, almost the entire cast seems stiff. The only vital and alive performances in the whole film are those of Ralph Richardson as Rudolf the Boss and Cedric Hardwicke as Thetocopolous, characters that Wells intended as the villains of the show. Both are celebrated actors who take to their roles with relish, although it probably was never Wells’s intention that they be the only ones present that the audience was drawn to. One other plus is Arthur Bliss’s excellent score (which incidentally had the distinction of being the first ever film score to be issued on an LP).

Understandably, Things to Come was such a uniquely original melange of creative circumstances that nobody has ever been brave enough to try remaking it. One semi-attempt to do so was the Canadian film The Shape of Things to Come (1979), which purports to be a sequel, but is in fact a tawdry and cheap space opera that has nothing to do with this film, bar the use of the names of two characters and is otherwise an attempt to shoehorn the legitimacy of the H.G. Wells name onto making a copycat of Star Wars (1977). There was also the unrelated Things to Come (1976), a pornographic film set in a dystopian future.

Trailer here