USA. 1971.

Crew

Director/Story – George Lucas, Screenplay – George Lucas & Walter Murch, Producer – Lawrence Sturhahn, Photography – Albert Kihn & Dave Meyers, Music – Lalo Schifrin, Art Direction – Michael Haller. Production Company – American Zoetrope.

Cast

Robert Duvall (THX 1138), Maggie McOmie (LUH 3417), Donald Pleasence (SEN 5451), Don Pedro Colley (SRT 5555), Ian Wolfe (PTO)

Plot

In the future, humanity lives a tranquilised life in an underground city, having been turned into the perfect consumer society with productivity and consumption figures to maintain, drugs to dampen behaviour and robot police to enforce the law. Sexual activity is illegal and sublimated by an ever-present supply of sex and sadism on holographic tv. THX 1138 becomes a criminal when his roommate LUH 3417 substitutes his tranqulisers, allowing them to engage in prohibited sexual activity. Caught, THX is jailed but makes an escape and goes on the run.

THX 1138 was George Lucas’s first film. The film originally began life as a student short THX1138: 4EB (1967) made by Lucas while at the University of Southern California film school. Lucas befriended Francis Ford Coppola and was hired to shoot a making of documentary of Coppola’s The Rain People (1969). Coppola, himself a former USC student, was still some time away from the big name that he would become with The Godfather (1972). While on the set, Lucas and Coppola became good friends, with Coppola making Lucas vice president when he formed his breakaway studio American Zoetrope in 1969. Lucas’s feature-length remake of his short film then became the first production of American Zoetrope.

THX 1138 is always a surprise to those who see it after discovering George Lucas’s name through Star Wars (1977). THX 1138 and Star Wars are completely different films. Whereas Star Wars created an entirely different type of filmmaking, THX 1138 was made in the 1970s when science-fiction saw a future ahead that existed only of technology overwhelming and dwarfing humanity – films like 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and The Andromeda Strain (1971) had defined the look of the future as one of blindingly clean, white antisepticism.

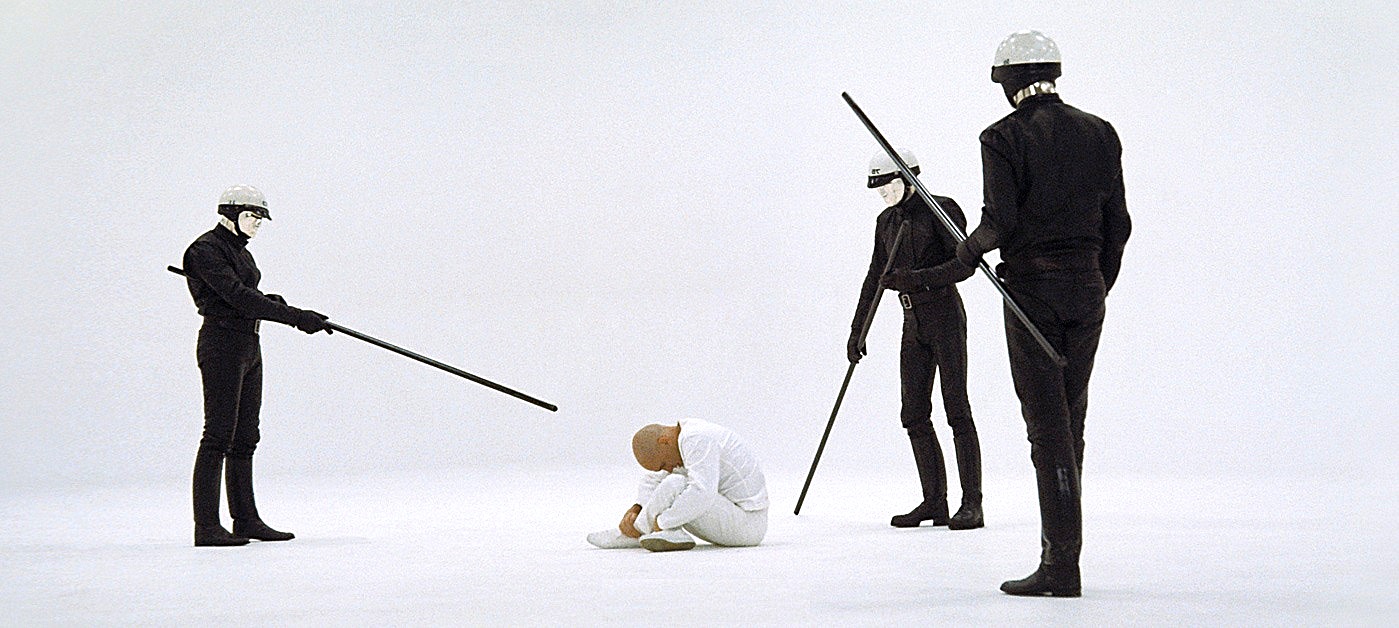

Here George Lucas’s visual stylism is overwhelming – THX 1138 is all shadowless white-on-white. Humanity is constantly being drowned out by the ordered chaos of flickering b/w tv screens and the chatter of disembodied voices on the soundtrack. Lucas deliberately fills the film with geometric patterns – an array of computer banks set out like a domino board, corridors of electronic circuitry trailing off into perspective or Robert Duvall’s head emerging from a line of identical cubicles. Particularly striking is a prison set in a featureless white-on-white void without shadow or any sense of perspective. The idea of the soulless future where people have no identity, just numbers and all work in uniformity has surprising number of similarities to the Russian dystopian novel We (1924) by Yevgeny Zamyatin.

There are some frightening images of depersonalised soullessness – of anonymous controllers watching tv monitors and dully commenting from off-screen who then chillingly, in equally monotonous voices, remotely shut down someone’s nervous system or produce muscular spasm tests by the manipulation of Robert Duvall’s brain. When it comes to the scenes of tenderness, George Lucas moves into closeup to focus on the raw texture of skin, of the faces and bald shaven heads of THX and LUH kissing and caressing, where the warmth of human skin makes sharp contrast to the ever-present white-on-white everywhere else.

There is a considerable lurking sense of black humour to THX 1138 – the constant public service announcements offering encouragement to increase production and reminding how much better this year’s fatality record is over last year’s; the visit to the electronic consumer church – a booth where a programmed voice hears THX’s confession and urges “Blessing of the masses. Buy more. Be happy”; or the faceless chromium robots politely talking to the people they arrest and where the hero eventually makes his escape when the robots have to turn back because the pursuit goes over-budget.

Symbolically, THX 1138 is a film about finding human individuality inside an impersonal and automated world. The main complaint regarding such a statement about individuality is that Robert Duvall’s THX remains a passive character throughout – most of his defiance of the system is something that he stumbles into by accident. THX makes a symbolic transcendental breakthrough at the end of the film – the last image is of him emerging to stand against a giant sunset, the first natural light we have seen in the film. It is a symbolic breakthrough but certainly not an emotional one and ultimately an ambiguous one where the world that THX has emerged into looks as blank and bare as the one he has just left and one wonders if his triumph is not merely a pyrrhic victory of the spirit.

The surprise that so many people watching THX 1138 find is that is as removed from the territory of the Star Wars series, Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and sequels and American Graffiti (1973) as George Lucas could possibly get. The Star Wars and Indiana Jones series are films that draw upon past movie-going thrills, while American Graffiti draws on the nostalgia of Lucas’s teens in the late 1950s. The common theme in all of these is George Lucas’s adolescence. Even visually, THX 1138 looks like it is made by a different filmmaker to the one who made the Star Wars films – while Star Wars, American Graffiti et al are commercially calculated mainstream films, THX 1138 comes with the aesthetic of an art film.

Moreover, it is a vision of the future that actively seems to rebuff the heroic earnestness of the Star Wars-type space opera. The theatrical version of THX 1138 even includes a pre-credits clip of scenes from the Buck Rogers (1939) serial (something excised from tv prints) as ironic contrast to show that this is not the way the future is going to turn out. (It should be noted that George Lucas originally conceived Star Wars after deciding he wanted to create a Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers film and found the rights too expensive to obtain).

THX 1138 is set in a bleak future where technology and the consumer society has entirely overwhelmed us and humanity is (visually at least) in danger of fading away into the clean antiseptic perfectionism of Utopia; Star Wars by contrast takes place in a world that is dirty, rundown and lived in and where humanity has definitely put technology in its place – the robots there are cute, cuddly sidekicks, not implacable steel-faced policemen. Star Wars and Buck Rogers celebrate a black-and-white humano-centric outlook, with heroes out to save the universe and defeat identifiably clearcut villains; in THX 1138, humanity has lost its identity, people have become featureless with shaven heads and letters and numbers instead of names. It is almost as though George Lucas, after making THX 1138, became so overwhelmed by his bleak vision of humanity’s non-future that he subsequently needed to retreat to a fairy-tale like purity – “a long, long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” – in order to be able to still find a sense of wonder again.

THX 1138 was not a success when it came out, although received acclaim in science-fiction circles. Its failure almost succeeded in bankrupting Francis Ford Coppola’s American Zoetrope studios – luckily, Coppola bounced back the following year with The Godfather and pushed Lucas to decide to go on a more commercial path with films that nostagically returned to the past (his own past, the story of his teenage years in American Graffiti, his love of science-fiction films in Star Wars). Of course, after the success of Lucas’s Star Wars, THX 1138 was resurrected and rescreened, although its deliberately dehumanised arthouse aesthetic proved baffling to the new generation of science-fiction enthusiasts who came expecting more in the way of intergalactic adventures. In 2004, George Lucas released a director’s cut of THX 1138, which expanded the background of several scenes with digital inserts.

THX 1138 is also interesting for the number of future names listed on the credits. Aside from George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and a young Robert Duvall, there is also Hal Barwood, later the co-writer/producer of genre films such as Dragonslayer (1981), Warning Sign (1985) and director of various Indiana Jones videogames for Lucas. Co-writing with George Lucas is Walter Murch, an acclaimed editor and sound editor on films such as American Graffiti, The English Patient (1996), and Coppola’s Godfather films and Apocalypse Now (1979), among others, who later became director with Disney’s underrated Return to Oz (1985).

THX 1138 was later parodied in Fanboys (2008).

George Lucas’s other genre films as director have been Star Wars (1977) and the Star Wars prequel trilogy, Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999), Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones (2002) and Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005). George Lucas’s other genre works as producer are:– the Star Wars sequels The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983), as well as various other animated series and spinoffs in the Star Wars universe; as producer of the Indiana Jones series consisting of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), the tv series The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles (1992-3) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (2023); the animated animated film Twice Upon a Time (1983); the disastrous Howard the Duck (1986); the fine Jim Henson fantasy Labyrinth (1986); the sword-and-sorcery adventure Willow (1988); and the animated Strange Magic (2015).

Trailer here