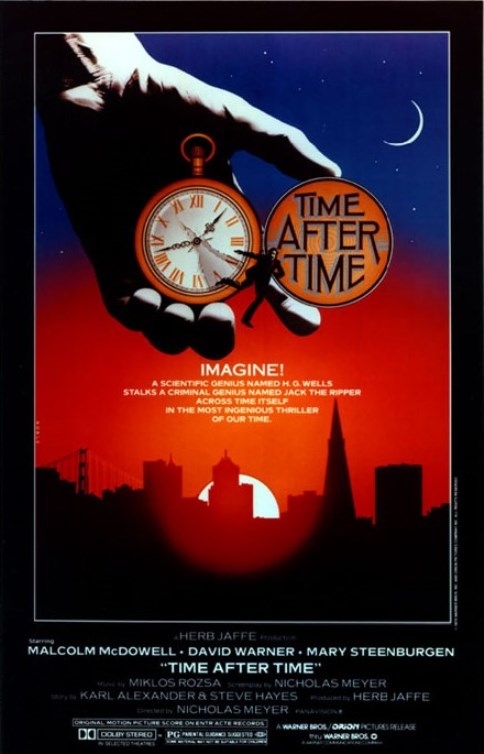

USA. 1979.

Crew

Director/Screenplay – Nicholas Meyer, Story – Karl Alexander & Steve Hayes, Producer – Herb Jaffe, Photography – Paul Lohmann, Music – Miklos Rozsa, Special Effects – Jim Blount & Larry Fuentes, Production Design – Edward C. Carfagno. Production Company – Orion Pictures.

Cast

Malcolm McDowell (H.G. Wells), Mary Steenburgen (Amy Robbins), David Warner (Dr Leslie John Stephenson)

Plot

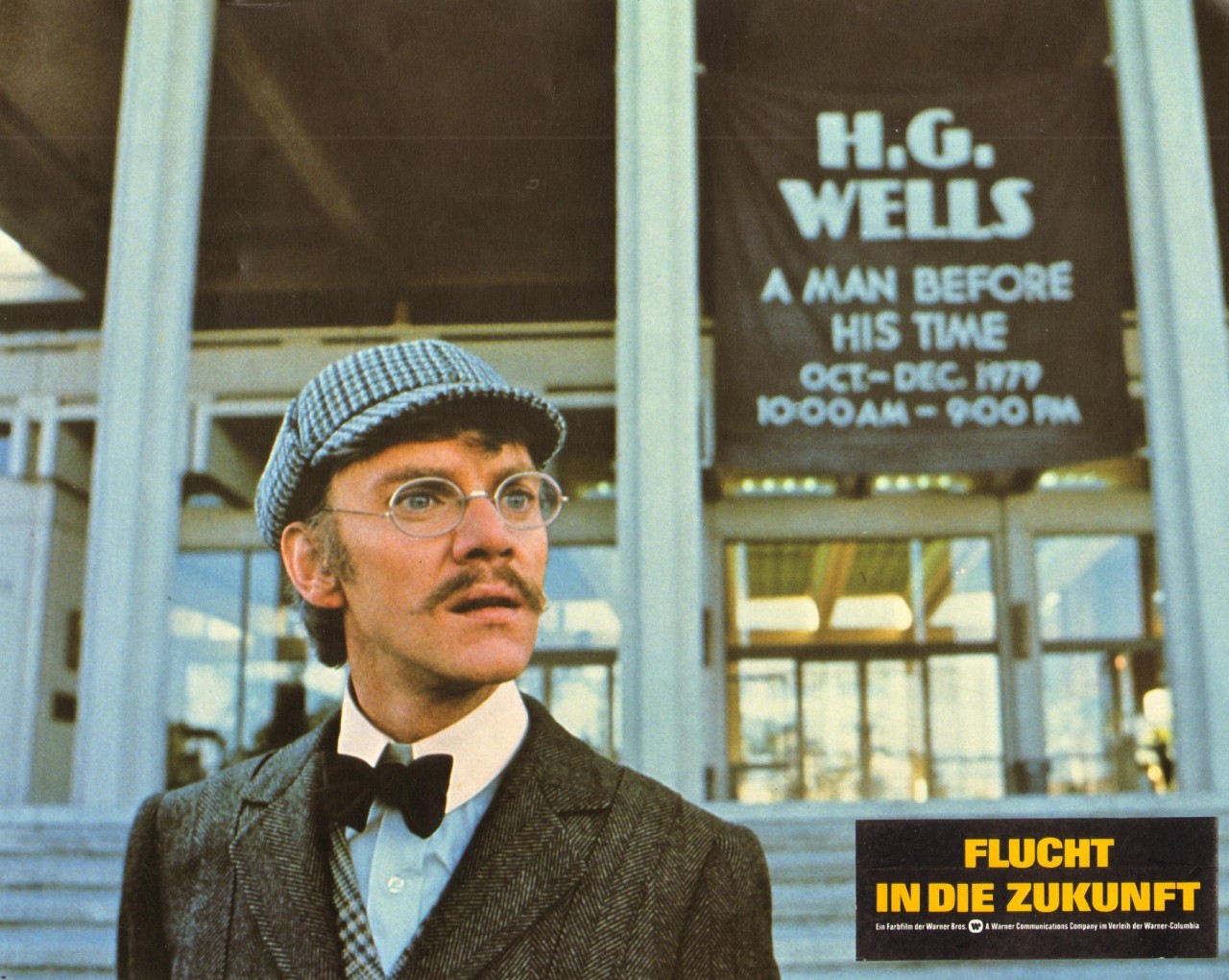

1893. Pursued by the police for the Jack the Ripper murders, Dr Leslie John Stephenson turns up to a dinner party thrown by his friend, the writer H.G. Wells. There Wells unveils his latest invention, a working time machine, but is interrupted by the police pursuing Stephenson. While Wells is occupied, Stephenson uses the time machine to escape into the future. Wells hurriedly pursues, ending up in a bewildering future San Francisco of 1979 where the time machine is part of an exhibition dedicated to his life and works. Disillusioned by seeing the reality of the Utopia he imagined, Wells becomes involved with bank teller Amy Robbins, while also trying to stop Stephenson who is revelling in the freedom and social disorder of the Twentieth Century. However, a trip into the future reveals that Amy will become Stephenson’s next victim.

Time After Time was the directorial debut of Nicholas Meyer, who has since become a regular genre contributor of some interest. Meyer’s earliest screenwriting job was Invasion of the Bee Girls (1973), an appealingly little B movie that is a more enjoyably than most people give it. (Even Meyer seems ashamed of it and it does not appear on his resume). Meyer also wrote the excellent tv movie The Night That Panicked America (1975) about the infamous 1938 Orson Welles War of the Worlds radio broadcast. Where Nicholas Meyer attracted attention was as a novelist with his two Sherlock Holmes pastiches The Seven Per Cent Solution (1973) and The West End Horror (1976). These more or less began the modern genre of Conan Doyle pastiches with Holmes encountering various characters out of Victorian fiction and history. In The Seven Per Cent Solution, Watson takes Holmes to Vienna to gain the help of Sigmund Freud in curing Holmes’s cocaine habit; while in The West End Horror, Holmes becomes involved in a theatre district murder mystery where he encounters the likes of Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker and George Bernard Shaw. The Seven Per Cent Solution was filmed as the highly entertaining The Seven Per Cent Solution (1976) with a screenplay by Meyer. The success of that gave Meyer the opportunity to make his directorial debut here with Time After Time.

The same conceptual game-playing behind Nicholas Meyer’s Holmes pastiches infects Time After Time, which he based on a synopsis presented to him by two film students. In Time After Time, noted science-fiction writer H.G. Wells has built his time machine in reality, his best friend turns out to be Jack the Ripper and the two take a trip to modern day San Francisco. Nicholas Meyer is less interested in the possibilities of the time travel device than he is in the possibilities offered once he gets the two characters into the present-day. (Although there are a couple of clever time paradox twists afforded by the script).

The fun to be had is in Meyer’s placing H.G. Wells’s quaint Fabian idealism against the modern world. “What have I done? I’ve loosed that bloody maniac upon Utopia,” Wells recoils in horror as he learns Stephenson has escaped into the future. The joke for us is the idea of Wells regarding modern day San Francisco as his Utopia. Later Wells, with his self-assured talk of free love, becomes distinctly embarrassed about Amy’s talk of her sex life, and frankly incredulous at her mention of a Sexual Revolution. There is a potent moment where David Warner’s Jack the Ripper sighs “This century has a home for me” and turns on the tv showing Warner Brothers cartoons, Jimi Hendrix smashing his guitar, war footage and the nightly news to make his point.

Nicholas Meyer tends to the journeyman-like as a director, but Time After Time is carried by the adroit ingenuity of the script and by the buoyant playing of all three of his principal cast. Malcolm McDowell gives a wonderfully perky performance (one of his best) as H.G. Wells. Opposite him, Mary Steenburgen is a ditzy delight. In a real world, she and Malcolm McDowell, cast here as lovers, met on set and were married soon after the film, and the romance between the two gives the film an authentic centre. David Warner turns on the dangerous intensity with a script that gives him full rein to go for all his worth.

Time After Time is less effective when one tries to consider it as historically credible. For one, it is hard to believe that an H.G. Wells who travelled forward to the present would then return to write such works of naively earnest future speculation as A Modern Utopia (1905), Men Like Gods (1923), The Shape of Things to Come (1933) and the film Things to Come (1936).

Wells and Jack the Ripper almost but do not quite mix. The Jack the Ripper killings occurred in 1888, although the film has them still continuing in 1893. In 1893, H.G. Wells was only 27 years old, had married his cousin and was working as a schoolteacher. Wells had only began publishing short fiction in 1893 and his first science-fiction novel The Time Machine, which made him famous, was not published until 1895. Here however the film casts Wells with Malcolm McDowell who was 36 years old, a decade older than Wells was in 1893, and has him already published and appearing to be making a reasonable success as an science-fiction writer some time earlier than in real life. Similarly, the life of Amy Catherine Robbins, who became H.G. Wells’s second wife, is well documented – she was a former student from a middle-class background and the two did not meet until 1895 – and it seems historically preposterous to suggest that she was a time traveller.

The film seems to have gone to assiduous lengths to avoid any design likeness to the time machine in the George Pal adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel The Time Machine (1960). The machine is now a more anonymous winged and hooded contraption vaguely resembling the head of a hawk rather than a splendid piece of rococo Victoriana. In a similar attempt to avoid any connection to the Pal film, which memorably depicted the time travel experience by speeded-up action taking place from the time travellers’ point-of-view, Meyer offers a more banal journey that is depicted via abstract plays of light and soundbite snippets from various historic radio broadcasts, which only draws attention to the concerted effort to differentiate itself from the Pal film and fails to hold the same imaginative thrust.

The George Pal film was also the first to directly associate H.G. Wells with his own time traveller. The sharp-eyed can spot a small brass plate on the time machine in the Pal film, which notes that the real name of the time traveller, who is only known as George, is H. George Wells. Since Time After Time, the idea of H.G. Wells himself as a time traveller has become a cliche as perpetuated by episodes of tv series such as Doctor Who (1963-89) and Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (1993-7), even Warehouse 13 (2009-14), which featured a Helena G. Wells.

Time After Time (2017) was tv series remake with Freddie Stroma as Wells and Josh Bowman in the Jack the Ripper role, although this was poorly received and lasted only twelve episodes.

Nicholas Meyer subsequently went onto develop a modestly successful career as a director. His next, best and most successful film was Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), regarded by most Trek fans as the best of the film series. Meyer then went onto the controversial tv movie The Day After (1983) about nuclear war. His other genre entries include script input on The Voyage Home: Star Trek IV (1986), the little seen Merchant-Ivory production The Deceivers (1988) about Indian Thuggee cults, before returning to helm the last of the classic Trek films Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (1991). He has also made a couple of comedies, the literary pastiche Volunteers (1985) and the spy spoof Company Business (1991), which did no business. From the late 1990s, Meyer moved away from directing to writing scripts such as Sommersby (1995), The Prince of Egypt (1998), The Human Stain (2003) and Houdini (tv mini-series, 2014), plus created the tv series Medici, Masters of Florence (2016– ). He also produced the epic tv mini-series The Odyssey (1997), the Arnold Schwarzenegger action vehicle Collateral Damage (2002) and the tv series Star Trek: Discovery (2017-24). Meyer has also returned to writing books with a further Sherlock Holmes pastiche The Canary Trainer (1993) where Holmes encounters The Phantom of the Opera.

Trailer here