USA. 1998.

Crew

Director – Peter Weir, Screenplay – Andrew Niccol, Producers – Edward S. Feldman, Andrew Niccol, Scott Rudin & Adam Schroeder, Photography – Peter Biziou, Music – Burkhard Dallwitz, Visual Effects Supervisor – Micheal J. McAlister, Visual Effects – Cinesite (Supervisor – Brad Kuehn), The Computer Film Co & Matte World Digital (Supervisor – Craig Barron), Special Effects Supervisor – Larz Anderson, Production Design – Dennis Gassner. Production Company – Paramount.

Cast

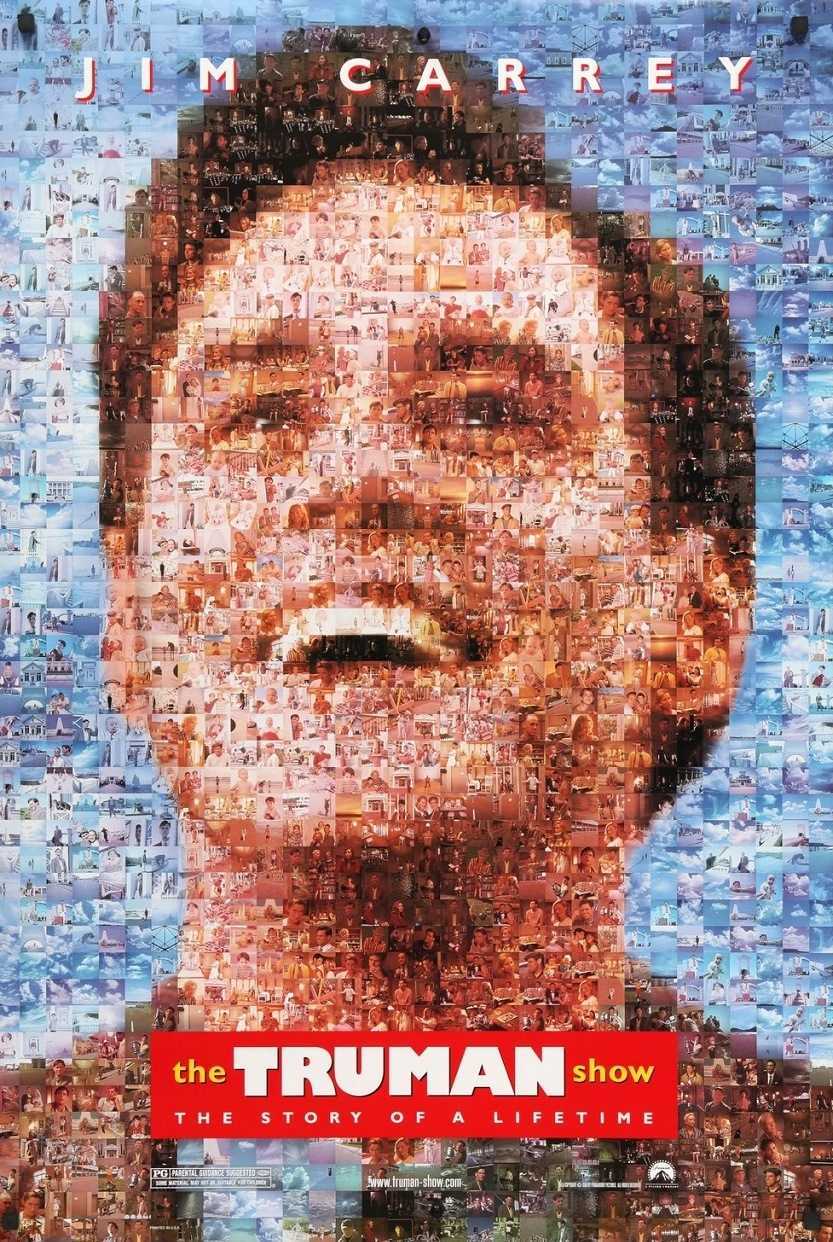

Jim Carrey (Truman Burbank), Ed Harris (Christof), Laura Linney (Meryl Burbank/Helen Gill), Noah Emmerich (Marlon/Louis Coltrane), Natascha McElhone (Lauren Garland/Sylvia)

Plot

Truman Burbank leads an ordinary untroubled life where he is as an insurance salesman and a married man. He is unaware that the entire town he lives in is an artificial construct, that everyone around him is an actor and that he is the subject of ‘The Truman Show’, a reality tv show that is watched by millions where everything that has happened since he was born has been scripted and his every reaction filmed. However, a series of mishaps – a fallen spotlight, his accidental tuning into a radio channel monitoring him, the reappearance of the actor playing his father who was killed off – make him begin to suspect the artificiality of his reality. He holds a secret longing for an extra that once tried to tell him the truth before she was caught. He now makes a concerted attempt to leave the town to find her, while the entire cast and crew make every effort to stop him.

The Truman Show comes written by New Zealander Andrew Niccol. Andrew Niccol made an impressive writing/directing debut with Gattaca (1997) and continues to impress again here. It is possible in The Truman Show that Andrew Niccol may have been inspired by Bernard Tavernier’s La Mort en Direct/Deathwatch (1980), which was set in a future where death was so rare that a woman with a rare terminal condition secretly became the subject of a tv show without her knowledge, and in particular the Philip K. Dick novel Time Out of Joint (1959). However, Andrew Niccol’s treatment of the theme in The Truman Show is remarkable and unique, making for that rarity of a film that is wholly original.

Indeed, with the sudden burst of reality tv shows during the summer of 2000, Survivor (2000– ), Big Brother (2000– ), The Truman Show proved to be a film that was uncannily prophetic. In a strange case of reality imitating fiction, not long after the reality tv fad hit someone came up with the idea of creating a Truman Show-styled reality tv show where a single contestant was surrounded by actors with The Joe Schmo Show (2003-4).

The central premise in The Truman Show is that Jim Carrey makes the discovery that his entire life is part of a tv show that is being scripted and played out by the people around him for a watching audience of billions. One is not spoiling any big surprise by telling this as the film’s publicity machine makes one aware of this from the start. Half the fun in the film comes from its’ setting up Jim Carrey’s idyllic lifestyle and then letting us watching the subtle intrusions the tv show make into the familiarity of its ‘reality’ – a crowd crossing the street suddenly freezing as a feedback whine jams their earpieces; people contriving to twist situations so they can stop and conduct product endorsements or push Jim Carrey into shot up against advertising billboards; the marvellous little excuses that keep getting invented every time something goes wrong or Carrey tries to leave the town – there is an hilarious visit to a travel agent’s office where the background is filled with travel posters that instead of offering invitations to sunny destinations advertise in the direst tones possible the hazards of travel.

The film even starts to cleverly play with audience perceptions – what one takes to be a standard musical score playing throughout is revealed as being played by background musicians; or the moment the hero’s best friend makes a heartfelt plea “Would I lie to you?” and the film pulls away to reveal this as a scripted line being fed into an earpiece. Most of the shots in the film mimic the camera shots of reality tv shows. Even the opening credits are for the tv show rather than for the film.

In The Truman Show, Peter Weir became the first director to tone down and obtain a relatively sane performance out of Jim Carrey. All of Jim Carrey’s previous films – The Mask (1994), The Cable Guy (1996), Liar Liar (1997) and the Ace Ventura movies – were founded as veritable amphitheatres for Carrey’s rafter-rattling histrionics. The Truman Show came about at a point when Carrey seemed to be making an effort to establish himself as a serious actor, with variable results, in the likes of Man on the Moon (1999), The Majestic (2001), Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) and The Number 23 (2007). Peter Weir was the first director to tone Jim Carrey’s irritatingly loud facial gymnastics down and allow the story on its own to carry the film. One cannot help but think a more average-seeming performer might have been better suited to the film but Carrey acquits himself capably upon this occasion – although ironically only by failing to dominate the film.

The conceptual audacity of both Gattaca and The Truman Show show Andrew Niccol as one of the most promising young writers around at the moment. Niccol has the ability of all good science-fiction writers to construct scenarios that are extrapolated from a single ‘What If’ premise – how would a genetic dropout survive in a world founded on genetic purity? what if a man found his entire life was being staged as a tv show? – and to work the premises to thoroughly logical conclusions. In both cases, Niccol creates heroes whose entire struggles centre on having to outwit and subvert an entire social order that is set against them.

Niccol went somewhat astray with his next genre directorial outing S1m0ne (2002), a comedy about a virtual Hollywood actress, but regained form with the excellent non-genre Lord of War (2005), a biting satire about the international arms trade and returned to science-fiction with In Time (2011), The Host (2013) and Anon (2018), as well as the non-genre Good Kill (2014) about modern drone warfare.

Australian director Peter Weir is mostly known for acclaimed mainstream works such as Gallipoli (1981), The Year of Living Dangerously (1983), Witness (1985), The Mosquito Coast (1986), Dead Poet’s Society (1989), Green Card (1990), Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (2003) and The Way Back (2010). During his earlier years in Australia, Weir made a number of fine forays into the genre with the bizarre The Cars That Ate Paris (1974) set in a town where the locals subsist by causing car crashes; the superb unexplained disappearance film The Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975); the eerie Aboriginal prophecy film The Last Wave (1977); and The Plumber (1978) about a sinister handyman.

(Winner in this site’s Top 10 Films of 1998 list. Winner for Best Supporting Actor (Ed Harris) and Nominee for Best Director (Peter Weir), Best Original Screenplay, Best Musical Score and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 1998 Awards).

Trailer here