USA. 1953.

Crew

Director – Byron Haskin, Screenplay – Barré Lyndon, Based on the Novel by H.G. Wells, Producer – George Pal, Photography – George Barnes, Music – Leslie Stevens, Photographic Effects – Ivyl Burke, Jan Domela, Gordon Jennings, Wallace Kelly & Irwin Roberts, Special Effects – Paul Lerpae, Bob Springfield & A. Edward Sutherland, Makeup Effects – Wally Westmore, Production Design – Albert Nozaki & Hal Pereira. Production Company – Paramount.

Cast

Gene Barry (Dr Clayton Forrester), Ann Robinson (Sylvia Van Buren), Les Tremayne (General Mann), Lewis Martin (Pastor Collins)

Plot

The inhabitants of a dying Mars arrive on Earth in projectiles, which are initially taken to be meteorites by astronomers. While on a fishing trip in California, scientist Dr Clayton Forrester is asked to investigate one of the meteorites that comes down in the area. A trio of locals go to greet the meteorite with a white flag but are incinerated by a heat ray from within. The military promptly move in. The meteorite then opens up, producing Martian flying machines. All across the world, the Martian war machines emerge and destroy all in their path with the heat rays. The military throw everything in their arsenal against the Martians, including the atomic bomb, but to no avail.

The War of the Worlds is the granddaddy of all alien invader films. There had been a handful of high-profile alien invader films before this with The Thing from Another World (1951), The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) and, coming out a few months earlier the same year as this, Invaders from Mars (1953) and It Came from Outer Space (1953). However, none of these ignited the formula – The Thing featured only one alien and kept it confined to an Arctic base, while The Day the Earth Stood Still featured a threat to humanity but the alien visitor turned out to be benevolent and the real threat to be human fear itself, and It Came from Outer Space featured seemingly sinister alien body snatchers but at the end revealed they only wanted to repair their spaceship and home. No – the alien invader genre, which in no time became the most prevalent theme in 1950s science-fiction, began proper here with The War of the Worlds.

The War of the Worlds was produced by George Pal (1908-80), a Hungarian emigre who had had success between 1932 and 1947 with a series of stop-motion animated short films he called Puppetoons. In the 1950s, Pal moved into live-action and produced Destination Moon (1950) and When Worlds Collide (1951), big-budget science-fiction films whose virtues were colour and spectacular special effects, even if they were wooden in terms of dramatics. As a result, George Pal became the most popular name in 1950s science-fiction and would go onto make a number of other classic genre films as producer and sometimes director. (See below for George Pal’s other titles).

The work that George Pal turned to was the H.G. Wells novel The War of the Worlds (1898), which in itself was the common ancestor of all alien invader stories. Indeed, H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds was the work that produced the central image of malevolent, tentacled little green men that became a cliche in 1930s pulp science-fiction. There had been plans to film the H.G. Wells novel over the previous three decades, with names like Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein, director of the silent classic Battleship Potemkin (1925), attached in the 1920s; Cecil B. De Mille of The Ten Commandments (1956) fame during the 1930s; stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, the cult figure behind The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958) and Clash of the Titans (1981), who conceived his own version and even shot some test footage in the 1940s (which still survives – see here on YouTube); and reportedly later Alfred Hitchcock, as well as producer Alexander Korda who collaborated with H.G. Wells on the visionary science-fiction film Things to Come (1936). Of course, on October 30, 1938, Orson Welles and his Mercury Theatre produced their famous radio adaptation, which caused panic due to Welles’s relaying it as a faked news broadcast that many thought to be the real thing.

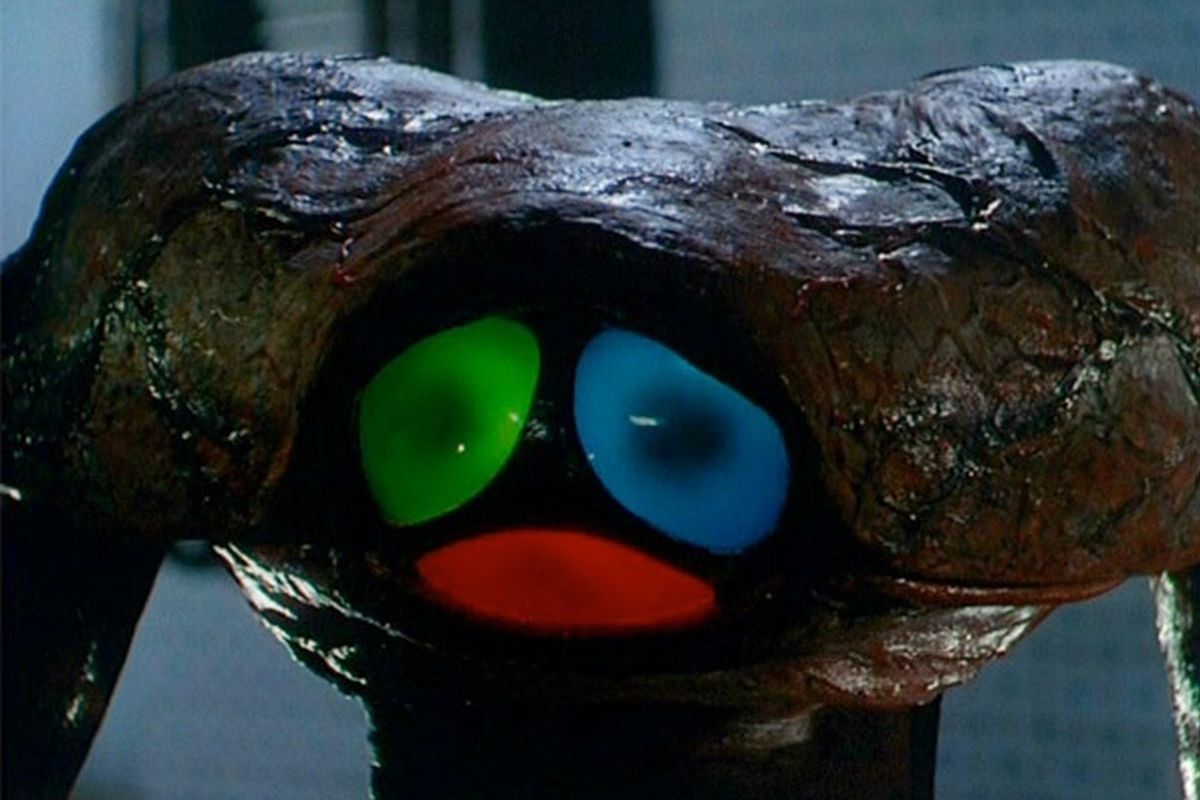

In a move that has brought an outcry from many purists, George Pal gave the H.G. Wells novel a facelift. Firstly, the Martian war machines were changed from tripods that strode across the landscape to sleek manta ray-like flying machines. No doubt, this was for ease of special effects. Even though Pal was a stop motion animator with his Puppetoon shorts, he clearly realised that stop motion animating tripedial war machines for the film would have been expensive and time-consuming. His solution was to eliminate the legs on the machines, allowing them to be brought to life using models on wires. (Although, if you look closely in one shot, you can see that the war machines do have tripods in the form of three electrical force ‘legs’ reaching down to the ground, although they never do in any subsequent shots. In an article by Pal in Famous Monsters of Filmland #140, he states that his original intention was to have the machines fly on three legs of electrical charge but the amount of voltage required was too unsafe for shooting on a soundstage. Instead he built three 42 inch models that were controlled like puppets on fifteen wires run overhead).

The most important of the changes made to the story was in transposing the setting from Wells’s contemporary Victorian England to Pal’s contemporary 1950s California. Again, this upset many purists (although it should also be noted that Orson Welles gave the story exactly the same contemporary updating in his radio broadcast). This at least keeps intact the metaphor of hubris that underlies the story, the shock sense of sleepy middle-class England being rent asunder. Wells’s The War of the Worlds is seen as a parable about the might of Victorian Imperialism being brought to its knees by an overwhelmingly technologically superior force; similarly, the update becomes a parable about the fragility of US post-War nationalism, fearful of its own vulnerability in the new Atomic Age. Despite changes made, the film at least uplifts the essence of the book to a different milieu and is faithful to the heart of what H.G. Wells wrote. The invasion here also takes in a far more international perspective – Wells never mentioned what happened to other countries – whereas the film cuts away to show other cities being obliterated, even if the action remains based in the US.

The film follows H.G. Wells reasonably closely when it comes to the landing of the meteors, the unscrewing of the cylinder, the emergence of the heatray eliminating all nearby and then the appearance of the machines. (One interesting addition during these scenes is the inclusion of radiation to the mix – something that was not discovered by Marie Curie until 1898, not long after H.G. Wells published the book). There is also an expansion of the scenes in the book where the narrator hides in a cellar with a fearful, mentally deranged curate. Now there is no curate and it is the hero (Gene Barry) and heroine (Ann Robinson) in the cellar and not only a probe entering but a Martian as well. This becomes such a classic scene that in rereading the book you tend to forget it was somewhat the lesser in print.

What is also now present in the story is a religious subtext that defies belief. George Pal’s films always seem caught between extraordinary leaps of imagination and a tremulous religious fear – Pal himself was a Catholic. See his Conquest of Space (1955) for a perfect example of religious fear overrunning a potentially good film. When H.G. Wells ended the book with the statement that the Martians were “defeated by the smallest thing in God’s creation” (bacteria), he was making an expression of irony, not one of religious belief. (Wells was a renowned atheist). The sense of irony is a small matter that seems to slip Pal and scriptwriter Barré Lyndon by. Instead, they take the statement with a deadening literalness and allow the religious subtext to take over the film. At one point, Ann Robinson states “I always knew if I hid in a church and prayed, my true love would find me there” – and of course Gene Barry later does exactly that. At the end, the Martian ships are finally brought symbolically crashing down outside the door of the church and afterwards humanity is shown standing on a hillside singing hymns in thanks for their delivery.

For H.G. Wells, the character of the curate, who descends into fear and meaningless babble during their imprisonment in the cellar, represents his contempt for religion; by contrast, the equivalent character of Pastor Martin here becomes completely the opposite – a solid, respected member of the community who bravely sacrifices his life to walk into the midst of danger and make a peaceful entreaty. Nevertheless, The War of the Worlds puts its finger exactly on the pulse of 1950s anxiety, of the imminent sense of the world about to collapse and of America as a nation clinging to its belief that is blessed by the Lord in hope for its delivery, something that was very much happening in the real world at the time with the upsurge in revivalism that brought to prominence people like Billy Graham.

The human side of things was never given much attention in George Pal’s films. But then this is not a film where one is paying much attention to the romance. For that matter, there were few in the way of characters or much development in the H.G. Wells novel – the narrator was an anonymous figure who was never even given a name. The film is a show being run by the effects people and as such it achieves rather well. The massive scenes of destruction are well orchestrated, despite frequently visible wires on the models. The war machines have a sinister elegance and come accompanied by a particularly memorable series of sound effects (which were achieved by guitar strings played backwards). The War of the Worlds was the most wide-ranging of alien invasions in the era – the others that followed lacked the lavish budgets to show such widespread scenes of devastation, let alone in most cases to even film in colour.

Byron Haskin was a staid director but here takes relish in all manner of gaudy and vivid colour schemes, with the entire film seemingly lit in mauves and greens. Haskin certainly rises to the occasion during the scenes in the farmhouse where he takes the film over into horror territory – the alien’s brief appearance and its spooking of Ann Robinson is something eerily effective. The classic imagery that Wells created on the page is vivid – the rising of the war machines on Horsell Common, the attack on the warship Thunder Child, the narrator and curate cowering in the cellar watching the Martians draining human blood outside. Haskin creates just as memorable a series of images here – Pastor Collins reciting the 23rd Psalm as he walks towards the war machines and is incinerated; the image of people approaching the crater with a white flag and being disintegrated; the dropping of the A-bomb and then the war machines emerging unscathed from the cloud of dust.

George Pal’s other genre films Destination Moon (1950), When Worlds Collide (1951), The Naked Jungle (1954), Conquest of Space (1955), tom thumb (1958), The Time Machine (1960), Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), 7 Faces of Dr Lao (1964), The Power (1968) and Doc Savage – The Man of Bronze (1975).

Byron Haskin worked with George Pal on several other occasions including The Naked Jungle, Conquest of Space and The Power. Haskin also directed a number of other genre films including Tarzan’s Peril (1951), From the Earth to the Moon (1958), Captain Sindbad (1963) and Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964), as well as episodes of the classic science-fiction anthology series The Outer Limits (1963-5).

The film was later sequelised as a routine tv series War of the Worlds (1988-90), which only had the name in common with the film. Here the invaders had abandoned their war machines and were standardised alien body snatchers being fought by a human resistance. Although the idea was mentioned several times during the immediate post-Star Wars (1977) boom, there had never been any cinematic remake of War of the Worlds up until 2005. This saw no less than three different adaptations of the story with Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster War of the Worlds (2005) starring Tom Cruise; the independently produced The War of the Worlds (2005) from Timothy Hines and his Pendragon Productions, which set out to film the H.G. Wells novel as written and was set in the Victorian period; and The Asylum’s low-budget modernised War of the Worlds (2005) starring C. Thomas Howell, which produced a sequel with War of the Worlds 2: The Next Wave (2008). Both the Spielberg and Pendragon versions return to H.G. Wells’s image of tripedial war machines, while The Asylum version features six-legged ones. This was followed by The War of the Worlds (2019), a three-part BBC tv mini-series set during the Victorian period; War of the Worlds (2019-22), a tv series that relocates action to the contemporary European Union; The Asylum’s modernised Alien Conquest (2021); the contemporary Young Adult film War of the Worlds: The Attack (2023); and the modernised War of the Worlds (2025) with Ice Cube.

There was also Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version of The War of the Worlds (2006), a dvd-released version of a stage performance of the best-selling 1977 musical album, the interesting War of the Worlds: Goliath (2012), an animated film set in an alternate history 1914 with Steampunk mecha taking on the second Martian invasion; and The Great Martian War: 1913-1917 (2013), a mocumentary retelling that blends CGI tripod war machines with WWI film footage. Other films include the Polish The War of the Worlds – Next Century (1981), which is not related to the Wells novel but is in fact a story about Martian invaders imposing media censorship, and The Night That Panicked America (1975), a tv movie depicting the hysteria surrounding the Orson Welles radio broadcast. A key scene from the film was also recreated in Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018).

Trailer here