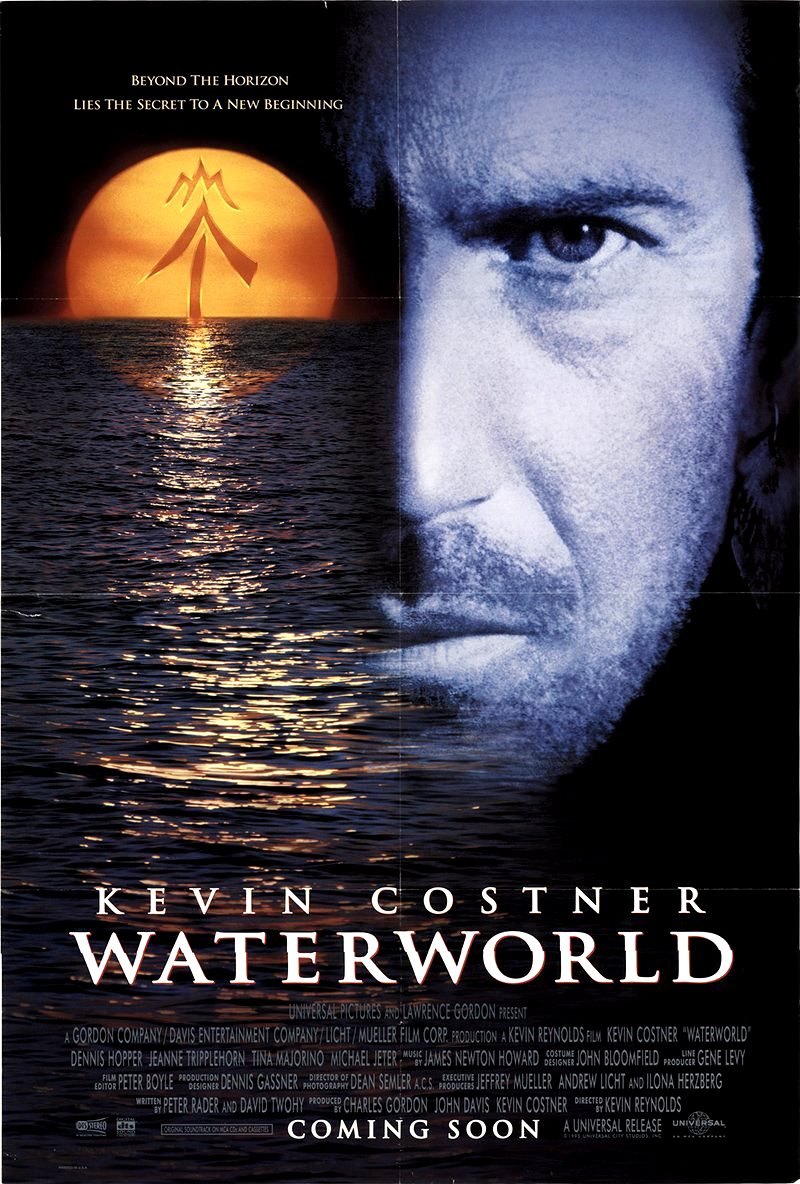

USA. 1995.

Crew

Director – Kevin Reynolds, Screenplay – Peter Rader & David Twohy, Producers – Kevin Costner, John Davis & Charles Gordon, Photography – Dean Semler, Music – James Newton Howard, Visual Effects Supervisor – Michael J. McAlister, Makeup Effects – The Burman Studio, Production Design – Dennis Gassner. Production Company – Gordon Co/Davis Entertainment/Licht-Mueller Film Corp.

Cast

Kevin Costner (The Mariner), Jeanne Tripplehorn (Helen), Dennis Hopper (The Deacon), Tina Majorino (Enola), Michael Jeter (Gregor)

Plot

The polar ice caps have melted and humanity is now forced to live upon the oceans where dry land is regarded as a myth and even a handful of dirt has become the equivalent of gold. A mariner arrives at The Atoll, a ramshackle floating traders’ habitat. The traders react with prejudice when they discover that the mariner is a mutation who has gills behind his ears that allow him to breathe underwater for extended periods of time. They are about to execute the mariner when The Atoll is attacked by The Smokers, a seagoing army commanded by the warlord known as The Deacon. Helen frees the mariner upon the agreement that he take her and her young ward Enola to safety. Out on the open sea aboard his trimaran, the mariner is reluctantly drawn out of his reclusiveness and comes to eventually care about the two of them. At the same time, The Smokers pursue them, The Deacon wanting Enola because she has a tattoo on her back that supposedly points the way to the mythical Dryland.

In these days of cinematic hardsell and mega-franchising, Waterworld is an intriguing example of the public’s prurient fascination with what happens when those in the media spotlight trip up almost entirely overwhelming a project. Even before Waterworld came out, who had not heard the behind-the-scenes story that played out through the likes of Entertainment This Week and the TV Guide gossip columns like a colossal real-life soap opera – Kevin Costner’s marriage break-up following a fling with a dancer on the set; his near-death encounter caught up in a squall while tied to the mast of his trimaran; the film’s massive set-backs, including the collapse of a multi-million dollar floating set during a hurricane; the firing of director Kevin Reynolds during the last weeks of shooting and how this split up the long time friendship between Reynolds and Costner; and Costner’s taking over the director’s chair in an effort to save the film.

Most of all there was the fascination with Waterworld‘s skyrocketing budget. Reliable estimates placed this around $170-180 million (although some quotes had it all the way up to $350 million). To place this in perspective, this was almost twice the figure of the world record for the previous most highly budgeted film and higher than the GNPs of Tonga and several African nations. (Although, if the Elizabeth Taylor Cleopatra (1963) had been made today its budget under inflation adjustment would have touched the $200 million mark and of course this figure would be overtaken by Titanic (1997) only a couple of years later and many other films in the decade since).

This negative hype was such that it almost entirely eclipsed what Waterworld was about. For example, in the months before the film’s premiere, I found it almost impossible to find an article that would tell me what the film’s plot was as opposed to discussing its behind-the-scenes-story. Without a doubt, Waterworld was a piece of epic miscalculation. The film needed to outsell Jurassic Park (1993) simply to break even. Even if Waterworld became one of the Top Ten box-office successes of all time when it came out, it still stood to make a massive financial loss. It is almost unimaginable to understand how such a colossus could have been created, even more so that the people involved did not see any of the warning signs earlier in the production – like maybe about the time the film started to escalate beyond its original $60 million budget.

I must admit to having considerable doubts about Waterworld from the start. It was not a good combination of elements. Kevin Costner’s box-office appeal had started to wane, with his then most recent films – the muchly underrated A Perfect World (1993), Wyatt Earp (1994) and The War (1994) – having all been a string of failures and Costner not having had a hit of any type since The Bodyguard (1992). The script barely seemed to operate above the level of a cartoon – in an interview, scriptwriter Peter Rader spoke proudly of original touches such as having the lead villain sit on a throne and waving a trident, or how Kevin Costner’s character’s big embarrassed secret was that he had painted a seahorse on the prow of his boat. (There was at least some hope for the script in that David Twohy, who wrote the inventive Warlock (1989), before going onto direct the intelligent and well above average likes of Timescape (1992), The Arrival (1996) and Pitch Black (2000), had been brought in to doctor Rader’s original script).

The worst omen of disaster was the involvement of director Kevin Reynolds. Kevin Reynolds was responsible for the Costner Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves (1991), a mindless and mythically self-promoting version of the legend that had been designed wholly as box-office spectacle, and Rapa Nui (1994), another piece of over-inflated fatuousness about Easter Island, carried solely by Reynolds’ fixation with epic-size imagery, and which, indicative of the Waterworld disaster, went way over budget and did virtually nil business. [Reynolds also wrote the script for John Milius’s ridiculous Communist Invasion film Red Dawn (1984), although did subsequently go onto make the halfway decent historical romance Tristan + Isolde (2006)].

Some critics, being the fickle bunch they were, created their own backlash against the anti-hype and tried to champion Waterworld. One hesitates to go that far. Waterworld is not a bad film by any means – it is just that one cannot help but feel it should have been more than it is. The story owes more than a good deal to Mad Max 2 (1981). In both films, there is a Clint Eastwood-styled loner hero – Kevin Costner’s character here literally has no name – who wanders the post-holocaust wastelands in his own vehicle. In both films, the hero gets to defend a small peaceful community as it is besieged by an army of wasteland crazies ruled by a bald-headed warlord. Everybody is fighting for a prized commodity – petrol in Mad Max 2, Dryland here. The hero befriends a wild child and a gadgeteer with a flying machine who appears to have a gear or two of his own loose. There are numerous vehicular chases and explosions. Why, both Waterworld and Mad Max 2 even have the same director of photography – Dean Semler.

Kevin Reynolds’ infatuation with epic size certainly makes all of Waterworld‘s budget show up on screen. The sets are mind-boggling in scale. The Smokers attack on The Atoll early in the film with flotillas of boats and jetbikes racing in in attack formation is a breathtaking set-piece, all filmed for maximum widescreen impact. There is one wondrous moment midway through the film where Kevin Costner takes Jeanne Tripplehorn down through the ruins of a city on the ocean floor.

However, such constant barrage of epic size eventually has a numbing effect. Scenes with seaplanes being swung around on the end of harpoon hooks or having their carriages ripped off during takeoff become gratuitous and seem indulgently inserted by a director who has become delirious with scale. Indeed, by the time of Kevin Costner’s climactic bungy-jump from a hot-air balloon, the audience reacts not with triumphant applause but instead in disbelieving laughter.

What is fun about Waterworld is its depictions of a ramshackle post-holocaust technology. From Kevin Costner’s marvellous erector-set trimaran to the Smoker fleet consisting of boats built up out of old truck beds and coal engines, there is a sense of a real-world operating beyond the expanse of the camera. The film opens with the memorable image of Kevin Costner pissing into a bottle, the camera following the trail of urine as it is passes through an elaborate filter system, which Costner then drinks. And there is the glorious moment when we see the rusted hulk of the Exxon Valdez setting sail with giant paddles through its hull just like a Roman slave galleon.

In the end though, Waterworld is a Mad Max copy. It is an expensive copy but it is still a copy. Indeed, the only real difference between Waterworld and the average Italian Mad Max copy is a $170 million instead of a $1 million budget. The sad thing about Waterworld‘s epic-scale, money-to-burn sensibility is how indicative it is of Hollywood thinking. Everything has been marshalled to the film’s cause – sets built that cost more than the budgets of most Hollywood films, a catering bill that spent daily more than the budgets of some B-movies, an army of stunt people. Everything that is except any genuine originality.

For the friendships and marriages that were split up throughout the film, the near-encounters with death, the massive amount of money that has been lost, it is sad to think that the artistic vision being sought throughout all this has not produced anything more than an efficient copy of another film.

Maelstrom: The Odyssey of Waterworld (2019) was a documentary about the problem-laden production. An episode of The Simpsons (1989– ) featured an amusing satire on Waterworld with a Waterworld videogame – one that costs 40 quarters and only allows 30 seconds of playtime.

(Nominee for Best Supporting Actor (Dennis Hopper) and Best Production Design at this site’s Best of 1995 Awards).

Trailer here