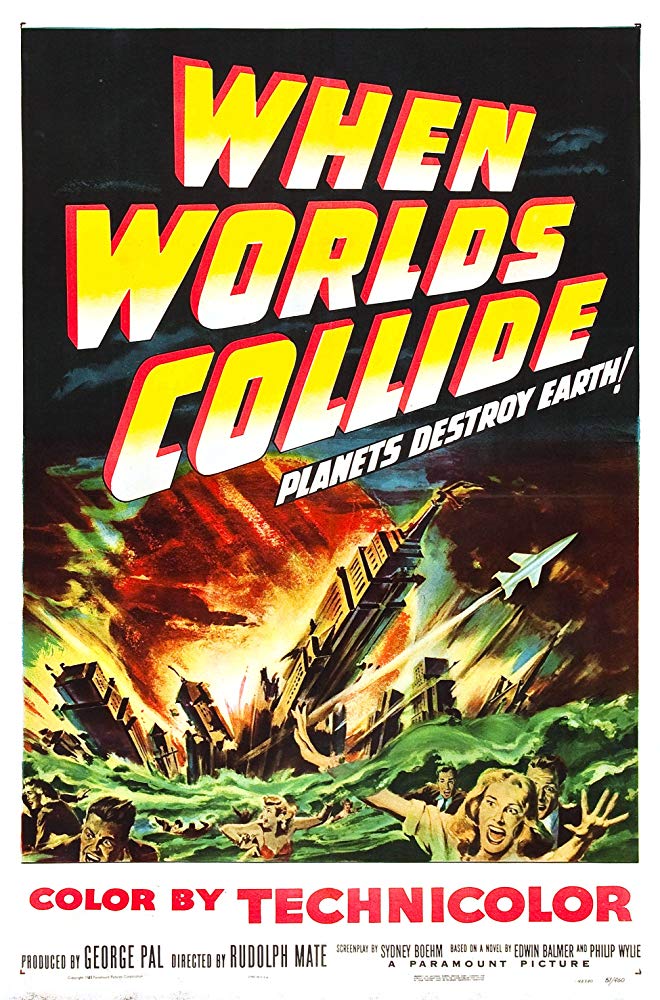

USA. 1951.

Crew

Director – Rudolf Maté, Screenplay – Sydney Boehm, Based on the Novel When Worlds Collide (1933) by Edwin Balmer & Philip Wylie, Producer – George Pal, Photography – Howard Greene & John F. Seitz, Music – Leith Stevens, Special Effects – Harry Barndollar & Gordon Jennings, Process Photography – Farciot Edouard, Art Direction – Al Nozaki & Hal Pereira. Production Company – Paramount.

Cast

Richard Derr (Dave Randall), Barbara Rush (Joyce Hendron), Larry Keating (Dr Hendron), Peter Hanson (Tony Drake), John Hoyt (Sydney Stanton)

Plot

Pilot Dave Randall is given the job of transporting a package of astronomical observations from Mount McKenna Observatory in South Africa to the US. Journalists are desperate to find the contents of the package, even offering him bribes. Afterwards, Randall discovers that the parcel contains calculations that prove that a wandering star Bellus and its orbiting planet Zyra are on a collision course with the Earth. Dr Hendron announces his findings before the UN but is denounced. However, a private group of financiers come to Hendron, offering to finance the building of a space ark so that a select few can relocate on Zyra after the destruction of the Earth. As the astral bodies near, they cause mass tidal waves and Hendron’s team race to complete construction on the ark. Hendron then announces a lottery to select those to go aboard.

When Worlds Collide was the second of George Pal’s science-fiction classics of the 1950s, made on the tail of the success of Destination Moon (1950). It was as big a success as Destination Moon had been and, like Destination Moon, went on to win that year’s Academy Award for Special Effects. It has all the same high points and the faults of George Pal’s productions – an emphasis on effects and wondrous spectacle but with a mawkish and wooden human element, as well as the same political naivete and religious underpinnings of any Pal production. Sitting among the horde of B-budget science-fiction films of the 1950s, When Worlds Collide is also an undeniable classic.

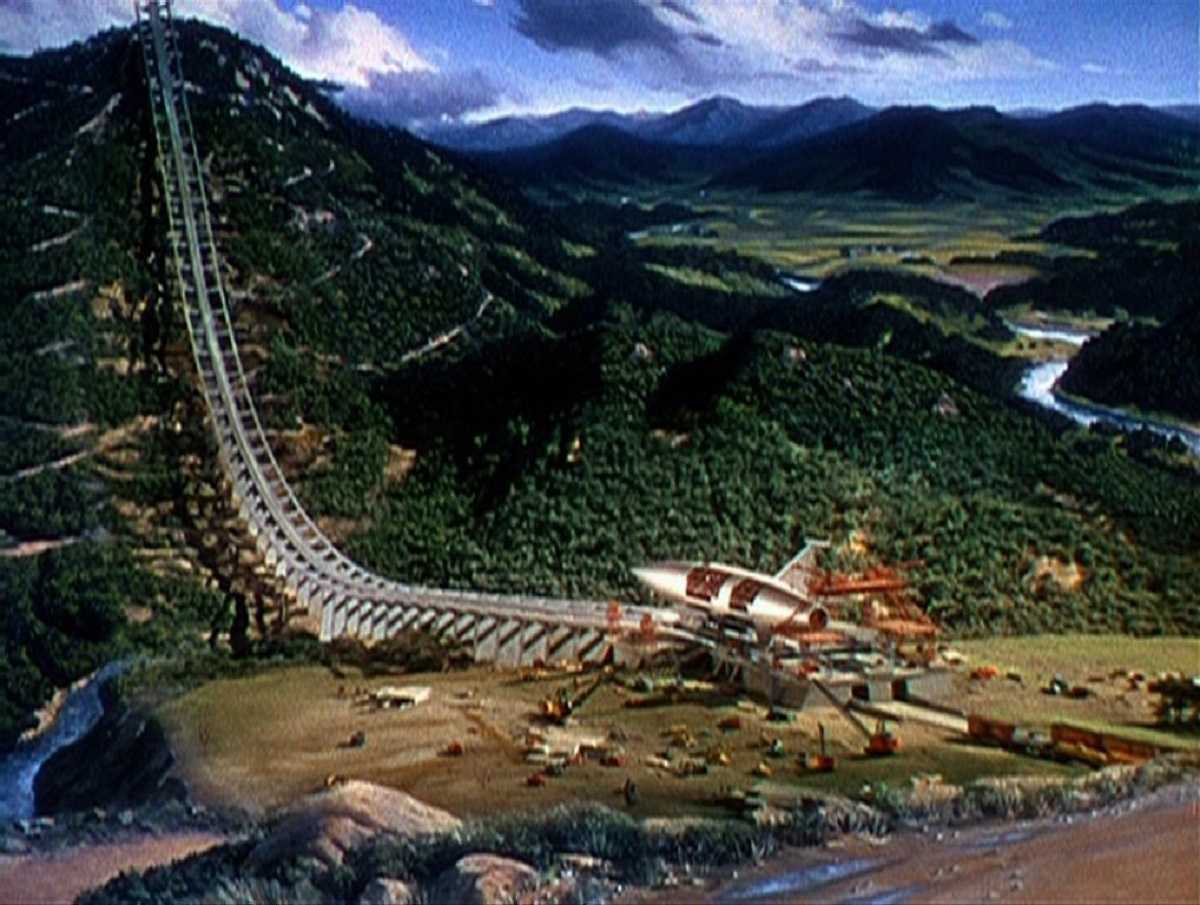

What George Pal and the directors who worked for him had, and in none of Pal’s films more so than here, was an eye for spectacle. The shots of the rocket towering above the camera as it is being built on the mountainside, of the camera panning along a bookshelf taking in the collected literary works of the human race as they are photocopied – is filmed with a feel for the momentous. The film’s images of mass devastation – waves crashing through the streets of New York, ships floating on their sides between skyscrapers – have an incredibly potent resonance. Stills from both these scenes have been reproduced numerous times in books and the images have an ability to speak on their own without people having seen the film. What is perhaps surprising – particularly in seeing When Worlds Collide after countless Irwin Allen-styled and modern CGI-driven disaster epics – is the sparseness with which actual disaster scenes are shown. Most surprisingly, the titular collision of worlds takes place entirely off-screen.

Where When Worlds Collide falls down is its human element. This comes written with a terrible corniness. It is doubtful, if faced with such a real crisis, the human race would go to their mass graves with such dignity, lack of anguish and all round decent behaviour as the human race depicted here does. There are one or two outbursts and a couple who are introduced for the sole purpose of being tragically separated by the lottery. However, there is no distress on the part of any of the central characters – indeed, the major crisis in the film seems to be on the part of the hero who is tragically upset when he is chosen to go and does not feel deservous of the privilege.

What is most interesting – no drama written today would ever be able to get away with it – is the scientist’s unquestioned stacking of the numbers that can go, he choosing himself, his daughter, her love interest, her ex-fiancee and a stray kid they pick up along the way. His right to choose these people is never questioned. A much more adventurous and interesting drama would have centred around him having to make choices to dump some of these people because they did not have the proper skills for the new world.

The character of Stanton – the hard-headed, self-interested philanthropist who is persuaded to help the mission but whose unpitying pragmatism about the need to stockpile guns comes true when those left behind decide to revolt – is one moment where the film briefly succeeds in doing something better than the book does. Although, the idea that the private sector would be benevolent enough to consider financing the apparently crackpot expedition when the governments refuse to – an idea also echoed in Pal’s Destination Moon – is a fairly laughable one, especially seeing the film today.

George Pal also adds a much heavier religious undertow than the original book (written in the 1933) had. One can see that the book naturally lends itself to religious allegory, a modern-day retelling of Noah’s Ark and all. (It was once optioned for filming by Cecil B. De Mille!!!). Far more than the book does, the film makes the connection that the destruction of the Earth and the salvation of a chosen few is divine justice. The point is unsubtly hammered home. The film opens on a Biblical quote: “And God looked upon the Earth and beheld it was corrupt for all flesh has corrupted his way upon the Earth” and the end with the survivors going out into a bright and shining new world is shown in terms of passover.

Throughout the 1960s, George Pal attempted to mount a sequel to When Worlds Collide, which would have been adapted directly from After Worlds Collide (1934), the sequel that the original book by its authors Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie wrote. However, in the 1960s, Pal’s importance as a producer began to wane and the project never got off the ground. In the late 1970s, Richard Zanuck and David Brown, the producers of Jaws (1975), attempted to mount a remake of When Worlds Collide without avail and in the 1990s the project finally mutated into the asteroid collision film Deep Impact (1998). This era of the CGI-driven spectacle movie however would provide a great opportunity for a full-blown remake and such a version has been announced for most of the 2000s/2010s by Stephen Sommers.

George Pal’s other genre films Destination Moon (1950), The War of the Worlds (1953), The Naked Jungle (1954), Conquest of Space (1955), tom thumb (1958), The Time Machine (1960), Atlantis, the Lost Continent (1961), The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), 7 Faces of Dr Lao (1964), The Power (1968) and Doc Savage – The Man of Bronze (1975).

Hungarian born Rudolph Maté (1898-1964) was a former cinematographer – he had lensed classic Carl Dryer works like The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928) and Vampyr (1932), before moving to Hollywood in the 1930s where he was nominated for an Academy Award for cinematography five times. He directed a number of other films during the era, including D.O.A. (1950), the Catholic miracle film Miracle in the Rain (1956) and the original The 300 Spartans (1962).

Trailer here